Donald Trump’s “reciprocal tariff” policy is intended to push back against globalization, but its inherent structural problems will only accelerate the trend of “de-Americanization” worldwide.

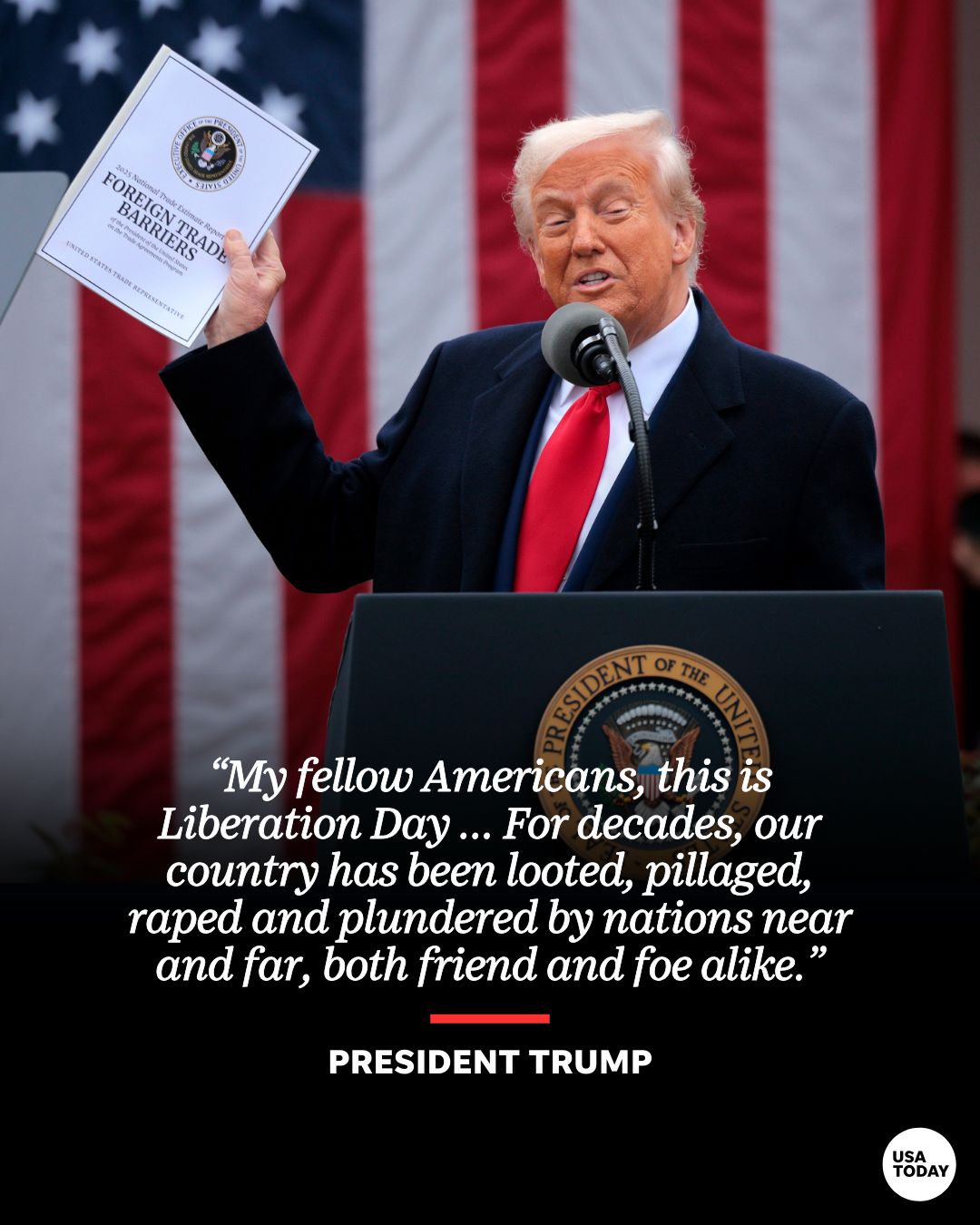

(Photo: USA TODAY)

On April 2, U.S. President Donald Trump announced an executive order imposing a sweeping set of so-called reciprocal tariffs on all imports into the country. The policy has dragged the world into a full-blown tariff war, and the United States is not likely to emerge as the winner.

Trump introduced two sets of tariffs applicable to different groups of countries: a 10 percent general or base tariff applied to imports from all countries, and a reciprocal tariff imposed on countries and regions with significant trade deficits with the United States, including China (145 percent), the European Union (20 percent), Vietnam (46 percent), Japan (24 percent) and India (26 percent). According to the Office of the United States Trade Representative, the primary targets of these tariffs are China, the European Union and Vietnam. Last year, U.S. imports from these amounted to $462.64 billion, $617.78 billion and $142.48 billion, respectively, and its trade deficits stood at $319.09 billion, $247.59 billion and $129.38 billion.

As it shifts from a country-by-country approach to a global carpet-bombing strategy, Trump’s tariff policy has stricken the world with unexpectedly high coverage and rates. From the “America first” trade policy to the Memorandum on Reciprocal Trade and Tariffs and the executive order on reciprocal tariffs, the policy came fast, making a huge impact on the global trade landscape and undermining the very foundation of the global trading system. It deviates from the WTO’s most favored nation treatment principle and has driven the U.S. weighted average tariff rate to 25.9 percent, surpassing the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930.

(Photo: USA TODAY)

The United States is not likely to come out on top, especially when compared with China. China has shown a stronger resilience to tariff shocks, as its exports to the United States are primarily everyday consumer goods. Thus it has less export dependency. Last year, China’s overall export dependency on the United States was approximately 14.7 percent. Only 95 products had a dependency rate greater than 50 percent, with their exports totaling $11.16 billion, or 2.13 percent of the nation’s total exports to the United States.

On the other hand, the United States relies heavily on Chinese imports for a significant range of products. In addition to daily necessities, the main U.S. imports include electric motors and electrical equipment. In 2024, U.S. dependency on Chinese imports was 13.8 percent. About 591 products had a dependency rate of more than 50 percent. These products accounted for $224.1 billion in imports, or about 48.4 percent of the U.S. imports from China. For the United States, China is a leading source of exports and even the leading supplier in some critical areas, such as electronic products, mechanical equipment and textiles.

China has all 41 industrial categories outlined in the United Nations industrial classification system and boasts comprehensive vertical integration capabilities ranging from chip packaging to automobile manufacturing. Its complete industrial chain makes it an irreplaceable player in global manufacturing. In the first quarter of this year, exports of Chinese goods grew by 6.9 percent, and the value of its imports and exports exceeded 10 trillion yuan ($1.37 trillion) for eight consecutive quarters. Meanwhile, its share in global trade remains stable and has even increased in recent years, as many countries and regions are highly dependent on its products. As the world’s largest trading nation in goods, China continues to enjoy a solid position in the global trade landscape.

At present, China is the world’s largest trading country for intermediate goods, the essential building blocks of the manufacturing industry. For example, among Chinese orders outsourced to Vietnam and Mexico, about 70 percent involves assembly work, while core components come from Chinese supply lines. This underscores China’s entrenched role at the heart of global industrial chains, a position that is difficult to replace in the short term.

As a result, the impact of manufacturing order shifts for export-oriented Chinese businesses is relatively limited. In addition, trade diversification has brought significant hedging effects. At present, the combined proportion of ASEAN, Middle Eastern and Latin American markets in China’s foreign trade increased from 32 percent in 2019 to 47 percent in 2023. The benefits of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement have demonstrated that expanding into diversified regional markets helps Chinese companies reduce their reliance dependence on the U.S. market.

Although Trump wants to brings manufacturing back home and enhance export competitiveness through protectionist reciprocal tariffs, the policy is expected to backfire, with a boomerang effect ultimately undermining the interests of the United States. In theory, imposing tariffs raises the prices of imported goods, thereby pressuring companies to shift production back to the United States. However, the burden of tariffs is in fact primarily borne by domestic consumers and companies. Tariffs don’t directly stimulate domestic manufacturing.

When the United States imposed tariffs on Chinese goods in 2018, U.S. importers largely passed the costs on to retailers and consumers through price hikes, instead of choosing to rebuild the domestic supply chain. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, manufacturing employment grew by only 0.5 percent during that period, far below expectations. The outcome indicates the failure of Trump’s tariff policy, as the mechanisms of cost transfers and price transmission did not function as expected.

The reshoring of manufacturing faces multiple obstacles, such as high costs and the inherent complexity of supply chains. In the United States, 30 percent of the intermediate products used in manufacturing are imported, meaning that tariffs directly push up the prices of industrial products. Large-scale high tariffs not only sharply increase production costs and weaken the competitiveness of U.S. companies but also encourage some multinational companies to circumvent tariffs by relocating their registrations and establishing production facilities overseas. Therefore, reciprocal tariffs will likely fail to bring manufacturing back home. In fact, they will likely divert production away.

The United States is changing from being a defender of the multilateral trading system to a disruptor. The Trump administration’s frequent changes of tariff policies — such as repeatedly increasing and then removing tariffs on Canada and Mexico — have seriously undermined the trust of its major trading partners, including its allies. As a matter of fact, some countries have begun to accelerate adjustments to their trade strategies with the United States and now seek new trading partners and cooperation mechanisms. In the long run, Trump’s reciprocal tariffs policy is intended to push back against globalization, but its inherent structural problems will only accelerate the trend of “de-Americanization” worldwide.