When U.S. President Joe Biden visited Europe in June — his first foreign trip — he tried to make the G7, NATO and U.S.-EU summits a highlight for democracy. He also tried to fortify his European allies as a camp against China by spinning China-related issues on the agenda as the antithesis of democracy. Clearly, Biden has become a direct successor to Trump in following the grand strategy of framing China-U.S. relations as a global contest between democratic and autocratic systems.

Ever since China and the U.S. established diplomatic relations 40-some years ago, China’s modernity and democratization has been a constant, obstinate obsession for the United States. Over that time, the U.S. focus on Chinese ideology was specifically about grading the country’s record on protecting human rights, safeguarding civic freedom and rectifying and remolding China from those perspectives.

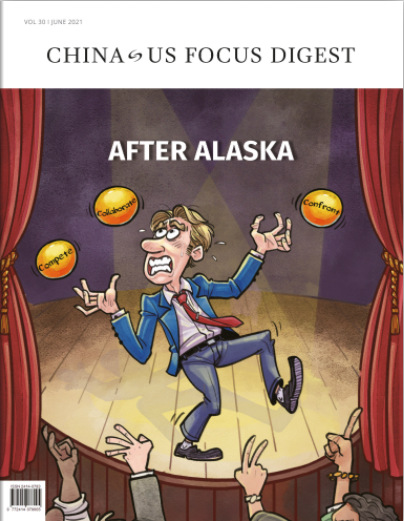

In a break with this historical approach, the Biden administration now attributes virtually every complaint about U.S.-China relations to China’s political system and official ideology, showing an inclination to expand and elevate ideological differences to the level of a Cold War-style, polarized competition between the U.S. and Chinese systems. Scholars such as Zack Cooper and Hal Brands even went to the extreme of prescribing the regime-failure theory in setting America’s China policy.

Click to read the latest China-US Focus Digest

The danger of a unilaterally ignited cold war is looming, and Biden is bent on setting up the democratic tent with allies to define the central clash of the 21st century as a contest between democracy and autocracy, and sharpening the confrontation with China to gain geopolitical leverage. It shows that the rise of China’s political influence as a natural result of its economic growth has heightened U.S. worries and anxieties. Making an issue of ideology serves the purpose of suppressing and undermining China strategically.

But this contest of systems will prove counterproductive for America, for it starts by exposing the intrinsic defects of U.S.-style democracy. It sounds like self-medication when the U.S. pronounces that democracy is “our most fundamental advantage” and “the single best way to realize the promise of our future,” as stated in the White House’s Interim National Security Strategic Guidance. The world has watched the tumultuous election of 2020 and the overrun Capitol in early 2021, as well as the repercussions of those events on the U.S. political system. Those are no fleeting memories with the change of one presidency, since Trump is neither the cause nor the cure for U.S. democratic dysfunction.

In the face of the real problem of social inequality and injustice between classes, ethnicities and generations, U.S.-style democracy has proved a problem rather than a solution, generating political polarization, sclerotic governance and violent populism unattended. According to a Pew Research Center poll released on March 31, a big majority of people in the U.S. (65%) say that the country’s political system needs major changes or needs to be completely reformed.

On the foreign front, the U.S. is of ill repute for transplanting democracy to other countries, often through the barrel of a gun. It goes against the very notion of human rights and democratic principles to use human rights as a justification for military interventions. Some American political pundits try to weasel their way out of the “hypocrisy” charge that the U.S. has received by saying that the U.S. need not be perfect in its own record of human rights before it polices others. But what has happened in Iraq and Syria is not a U.S. domestic matter. These war-torn countries, and the rest of the world, do care if the U.S. is hypocritical or not.

A contest of systems does not echo the appeals of most U.S. allies and “middle” countries about the conduct of foreign affairs. While these countries face the dilemma of choosing sides between China and the U.S., their independent foreign policy choices will not necessarily be based on ideological affinity with either one of those two powers but rather on pursuit of their own national interest in improving domestic livelihoods and promoting people’s well-being.

While Biden was trying to rebrand the G7 as a group of “like-minded democracies,” as opposed to a group of “highly industrialized nations,” French President Emmanuel Macron was quick to clarify that the G7 is not a club hostile to China. And German Chancellor Angela Merkel reiterated the importance of working with China to tackle climate change, biodiversity and other global challenges. It shows that allies do have much in common with the U.S., but they clearly differ from the U.S. on China policy.

At least part of the reason why the U.S. has refrained from articulating a clear strategy of systemic confrontation against China is that it can only step back a bit to find middle ground with allies to establish a facade of democratic solidarity. This also illustrates the tremendous hard work that still lies ahead if Biden is to create a D10, a T12, or organize some other larger democratic coalition such as the global “summit of democracies.”

“Democracy” is not even a sufficient condition to hold the U.S. alliance together. The highest principle guiding U.S. policy toward its allies comes down to its strategic interests and needs. Ideological homogeneity is just a secondary consideration. For example, most of U.S. security cooperation partners and non-NATO allies in the Middle East and Southeast Asia have different political systems. The U.S. is always ready for pragmatic compromises to build coalitions with such countries (including with China in the 1970s). Nowadays, as U.S. ability to provide a security umbrella and economic benefits to its allies and partners decreases, the latter may follow Washington in expressing loyalty verbally. However, when it comes to real and tangible security and the economic investment to back up a contest of systems against China, the spotlight remains on the U.S.

Ultimately, by organizing a “democratic world” vis-a-vis China, the U.S. is attempting to cap China’s economic and technological development through a modularized coalition approach. The crux of the matter is to constrain or even exclude China’s from international rule-making within various clubs dealing with 5G technologies, digital economy, data privacy, cybersecurity, etc. China must avoid stepping into the trap of a systems contest, and focus on optimizing its economic and industrial policies to seize the initiative of further development. In the meantime, it is also incumbent on China to challenge the ideological prejudice that the U.S. still clings to.

The Cold War is past. The artificial dividing line between the East and the West has come down. With all kinds of new ideas and ideological consciousness surging up, and integrated in coexistence, today’s international relations are becoming more balanced. No force can stop people from reexamining ideal approaches to governance and the core concepts of democracy.

China, with its ascending power, is obliged to explain itself to the world, including its world views. In that effort, it is high time for it to remove the shackles of ideological demonization imposed by the U.S. and contribute convincing values and ideas to the world.