China’s rise to dominance in electric vehicles, much like Japan’s earlier challenge to U.S. automakers, has prompted an aggressive American response, including tariffs and industrial policy aimed at countering Beijing. But the past offers a valuable lens for understanding today’s EV race and what may come next.

Despite tariffs and other hostilities from across the continent and oceans, China’s EV players have been crushing it, for some ironically market-based reasons: a large and digitally-friendly population and the world’s best manufacturing ecosystem.

That success isn't just a product of market dynamics, though — it's also the result of a public-sector strategic focus on EV for more than 20 years. (I’ll review the net impact of subsidies and other government support in part two of this essay – they tell part of the story, but far from the whole one.) The Tenth Five Year Plan, launched in 2001, identified EV as a priority research field. Wan Gang, considered the father of China’s EV development, earned a PhD in mechanical engineering in Germany before Audi won a bidding war to hire him in 1991. At the end of his auto-focused 15 years in Germany, Wan submitted a proposal in the year 2000 to China’s State Council for the country to develop EV as the promising mobility sector for China’s future. His proposal helped shape national policy, and in 2007, he was appointed head of China’s Ministry of Science and Technology.

U.S. policy and orientation toward EV has been convoluted – at times favoring EV development, and at other times discouraging it. Major EV-related initiatives since 2020 have included the Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act (tax credits for EV purchase) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (EV charging stations). Other regulations placed increasing levels of tax and eventual outright prohibition on internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles.

Notoriously, the U.S. government has also targeted the Chinese EV sector in particular, with rapidly increasing tariffs on the vehicles and batteries, and also a 2023 law stating that “vehicles placed in service beginning in 2024 must not have batteries containing battery components manufactured or assembled by a foreign entity of concern (FEOC). In addition, vehicles placed in service beginning in 2025 must have no batteries containing applicable critical minerals extracted, processed, or recycled by a FEOC.”

Facing the emerging EV phenomenon, the U.S. auto sector has behaved largely as it did when it faced the rising Japanese auto makers starting in the 1970s. According to Bill Russo, founder of Automobility and a globally recognized authority on the electric vehicle transition, EV “efforts by U.S. automakers appear largely performative—focused primarily on higher-margin segments, allowing them to maintain the status quo across their broader product lines.”

The example of Japanese versus U.S. automakers from decades ago offers valuable insight into what’s happening now and what’s likely to happen in the future regarding EV. Now as then, the United States plumps for policy approaches to structural challenges – then the increasing superiority of the Japanese cars, now the inexorable EV revolution, and a Chinese EV sector that leads in every way: from design innovation, to supply chain expertise – from the cobalt and lithium to the showroom floor – to an organized and strategic development of the sector that has overwhelming national support.

The U.S. approach is already proving as detrimental to the U.S. auto sector in particular as the misfocus on policy did 40 years ago. But this time, the damage to the U.S. economy and global stature will become much more pervasive, because while the Japanese auto makers were better by degree, improving the design and manufacture of ICE vehicles, the EV revolution is transforming human mobility as profoundly as any since perhaps the dawn of the Industrial Revolution — certainly since mass production in the U.S. auto sector changed the world a century ago.

Part one of this two-part essay looks back to the late 20th century, to understand the Japanese automakers’ ascent and what we may learn from it. Part two looks at the EV sector today, to understand why the Chinese brands are already so dominant, and what that portends for the future.

Part I: The Previous Asian Upstart

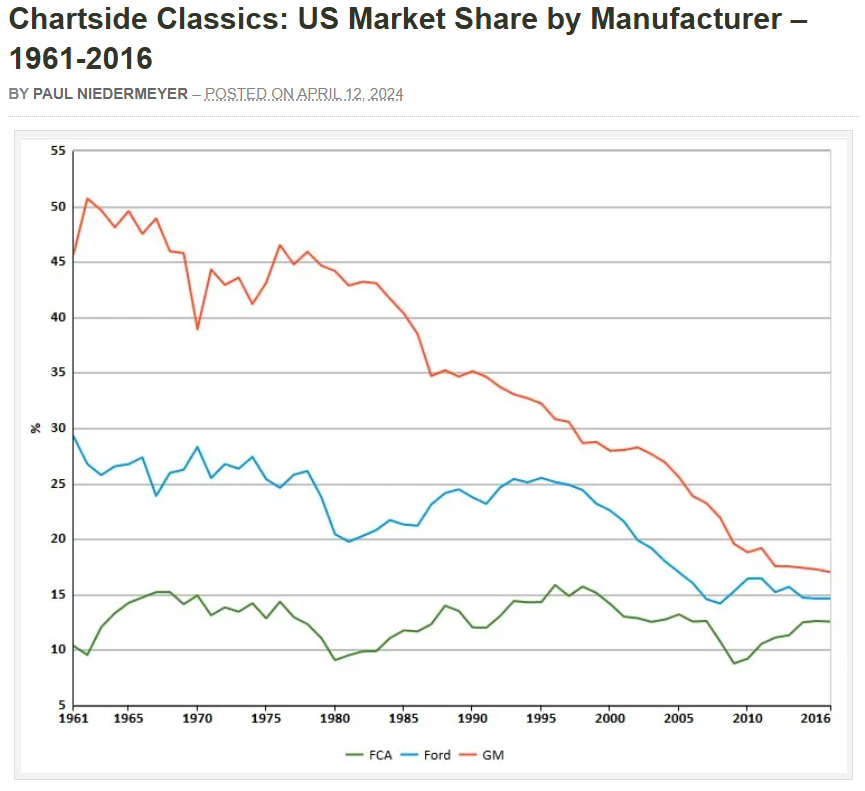

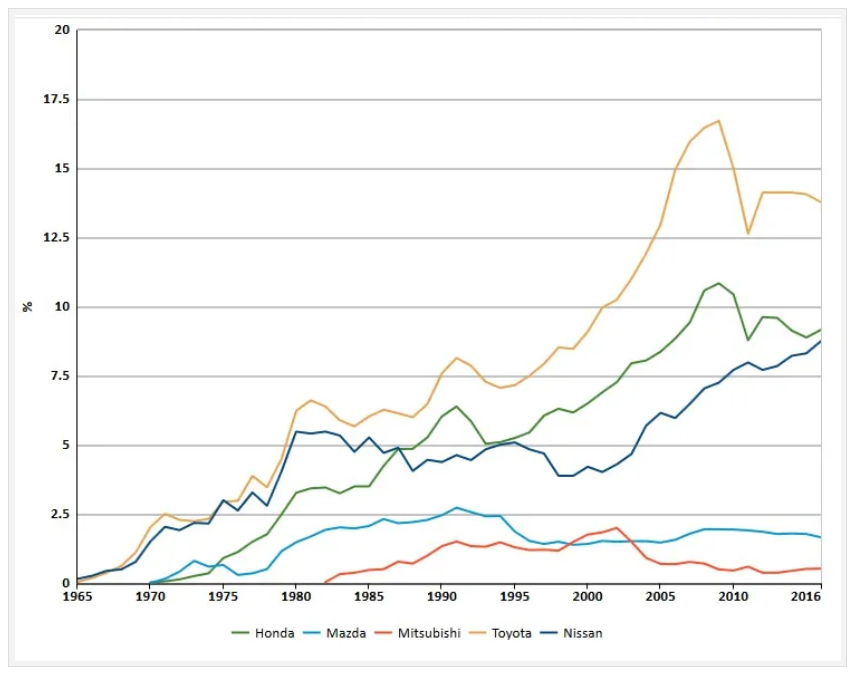

At the end of the 1960s, the U.S. Big Three (Ford, GM and Chrysler) had roughly 75% of the global market and nearly 90% of the U.S. market. GM alone, then the largest global brand by volume, commanded nearly 50% of U.S. sales. The Japanese makers had only just arrived, bringing cars that those of us alive in the U.S. at the time laughed at – we thought they were cheap cars made by untrustworthy foreigners who, we believed, cheated on intellectual property. But by 1970, the Japanese brands’ global share had surged past previously No. 2 Germany, on the back of a fast-growing domestic market and increasing sales in less-developed countries, both propelled by a level of cost performance – quality over price – that the developed world would soon discover.

By the early 1980s, the derision and dismissal had disappeared. The Japanese brands had become No. 1 globally. More tellingly, Japanese imports to the United States exceeded 20% of total market that year, at the expense of the Big Three, whose share had declined to below 75%. Two oil shocks, 1973 and 1979, helped a lot – few cared about fuel efficiency in 1970, but everyone did by 1980, and the Japanese brands therefore became a lot more attractive.

No one should doubt that Japanese policy restricted foreign automakers from gaining share in Japan and that Japanese export policy (hence Japanese citizenry) subsidized Japanese automakers. Polities that venerate what Marco Rubio referred to, in his better days, as “free market fundamentalism” are like evangelists everywhere – they simply cannot understand when others don’t adhere to the faith, and therefore abhor such industrial policy as Japan adopted from just after the war. But arguing that emerging economies shouldn’t engage in domestic protectionism or export subsidies is a fool’s errand.

And in the case of the Japanese automakers, such arguments were also tangential. One may immediately ignore anyone who claims that import barriers account for most of the low sales volume of U.S. brands in Japan. Anyone who has ever witnessed the Japanese auto environment immediately notes that a) the Japanese drive on the left side of the road, and U.S. automakers disdain to adapt with right-hand steering wheel models, b) Japanese streets and parking areas are tighter (a third of all cars sold in Japan are “kei” (light) — much smaller than a standard auto and a category never touched by the U.S. automakers), and c) the customer journey for purchase and service is, well, Japanese, with all that implies, and the U.S. brands have a widespread, well-earned reputation for fuel thirst and unreliability.

An MIT study, published in 1988, reviews the “myths and realities” about the ascent of Japanese auto brands – the myth being that some sort of essentialist argument about the Japanese being ‘different’, or that export subsidies and such, explained the Japanese automakers’ ascent, the reality being that the Japanese were simply and dramatically better at producing quality cars, cost-effectively. The MIT study is only one bit in an entire, er, carload of diligent research reaching the same conclusion.

Nonetheless, the U.S. automakers, and Congress, largely sought policy solutions to the threat to the automakers’ sales and profitability. Then as now, they found it hard to acknowledge that foreigners were doing something better. In 1993, veteran economics researcher Hobart Rowan wrote, “Especially, American executives scoffed at the foolish idea that any other country, especially Japan, which had a post-World War II record of producing shoddy goods, could compete.” Rowan’s article eulogized W. Edwards Deming (1900 – 1993), now recognized worldwide as a prescient prophet of quality manufacturing, inspiration for the now-famous Toyota Production System, but shunned by manufacturers in his U.S. homeland through the 1970s. The Japanese manufacturing sector eagerly studied Deming from the immediate post-war period, when Deming was posted to the devastated country.

By 1981, Ford in particular was skirting bankruptcy and, belatedly, decided to hire Deming and follow his now-proven methods. Ford became the most profitable of the Big Three within five years, but the others, and the U.S. policymakers, kept a focus on trade protection, which led to a combination of exchange rate adjustments (notably and eventually the 1985 Plaza Accords) import caps and domestic production content requirements. By the time of Plaza, the Big Three Japanese brands – Toyota, Nissan and Honda – had all begun manufacturing in the United States.

From the 1980s on, GM’s share of the U.S. market dropped like a stone, to below 20% in 2o10. Ford and Chrysler gained share at GM’s expense in the 1980s, but resumed a share decline from the mid 1990s, to below 15%. Chrysler went bankrupt after the financial crisis of 2008, which also led to a US$20 billion taxpayer bailout of the industry.

Toyota, on the other hand, took pole position as the world’s largest automaker by volume in the late 2000s, a title it has mostly held since. Toyota briefly surpassed GM in the U.S. market in the late 2010s, and the Japanese brands overall now enjoy about 30% of the U.S. market. Moreover, the Japanese brands are by far the most ‘American’ cars, as ranked by Cars.com, who evaluate based on “assembly location, parts content, engine origin, transmission origin and U.S. manufacturing workforce.” Honda and Tesla each have three in the top 10, but Honda’s models together far outsell the Teslas, while about 300,000 people in the United States bought the Toyota Camry (No. 7 on the Cars.com list) in 2024, more than double the sales of the entire Tesla line. In the top 20, we see eight Honda/Acura models and five Toyota/Lexus models – not a single GM or Ford, only one Jeep and one Chrysler. Plus, the Japanese brands now manufacture about 30% of all cars sold in the United States. The Japanese brands excel at making cars in the United States, for the United States.

One can still find apologists for the U.S. auto industry here and there claiming that we may blame nefarious Japanese behavior and an overly complacent regulatory environment in the United States for the Japanese brands’ ascendency. In fact, as MIT and many others have repeatedly demonstrated, the Japanese brands brought people in the United States, and worldwide, a superior product. One cannot otherwise explain the enormity of the shift in market share from the late 1960s through today. That should sufficiently nail the coffin of the idea of import cheating, or some vaguely racist assertion about the Japanese workforce, being a substantial explanation for those brands’ success.

Fast forward three decades, and we see a remarkably similar phenomenon, this time in the EV world, although the impact of Chinese enterprises’ dominance of the sector will be an order of magnitude greater on the world and may well nail another coffin – that of the U.S. automakers as we know them now. They have apparently learned nothing from what happened previously. We continue with that discussion in Part 2.