China’s new export licensing system strengthens its control over key rare earth elements, deepening supply chain risks. Although new processing facilities are emerging abroad, they won’t soon offset China’s dominance, prolonging global uncertainty.

On April 4, 2025, China announced the establishment of a new licensing system for the export of certain rare earth oxides, alloys, and magnets. Specifically, the new export licenses apply to 7 of 17 rare earth elements (REEs), all of which are medium and heavy rare earths: samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium.

As the new restrictions were announced, the initial interpretation was that they were in direct retaliation for U.S. tariffs imposed by President Donald Trump days earlier. But the establishment of this system was likely in the works for some time and is dictated by different time constraints than Trump’s trade war. In fact, there remains much confusion as to what exactly is happening in the rare earth trade and where things could be headed.

Perhaps the least understood aspect is how a crucial input that sustains global supply chains across industries faces a pronounced supply choke point. In other words, without critical rare earth materials, industries from semiconductors to electric vehicles, robotics, drones, aerospace, and defense could come to a halt.

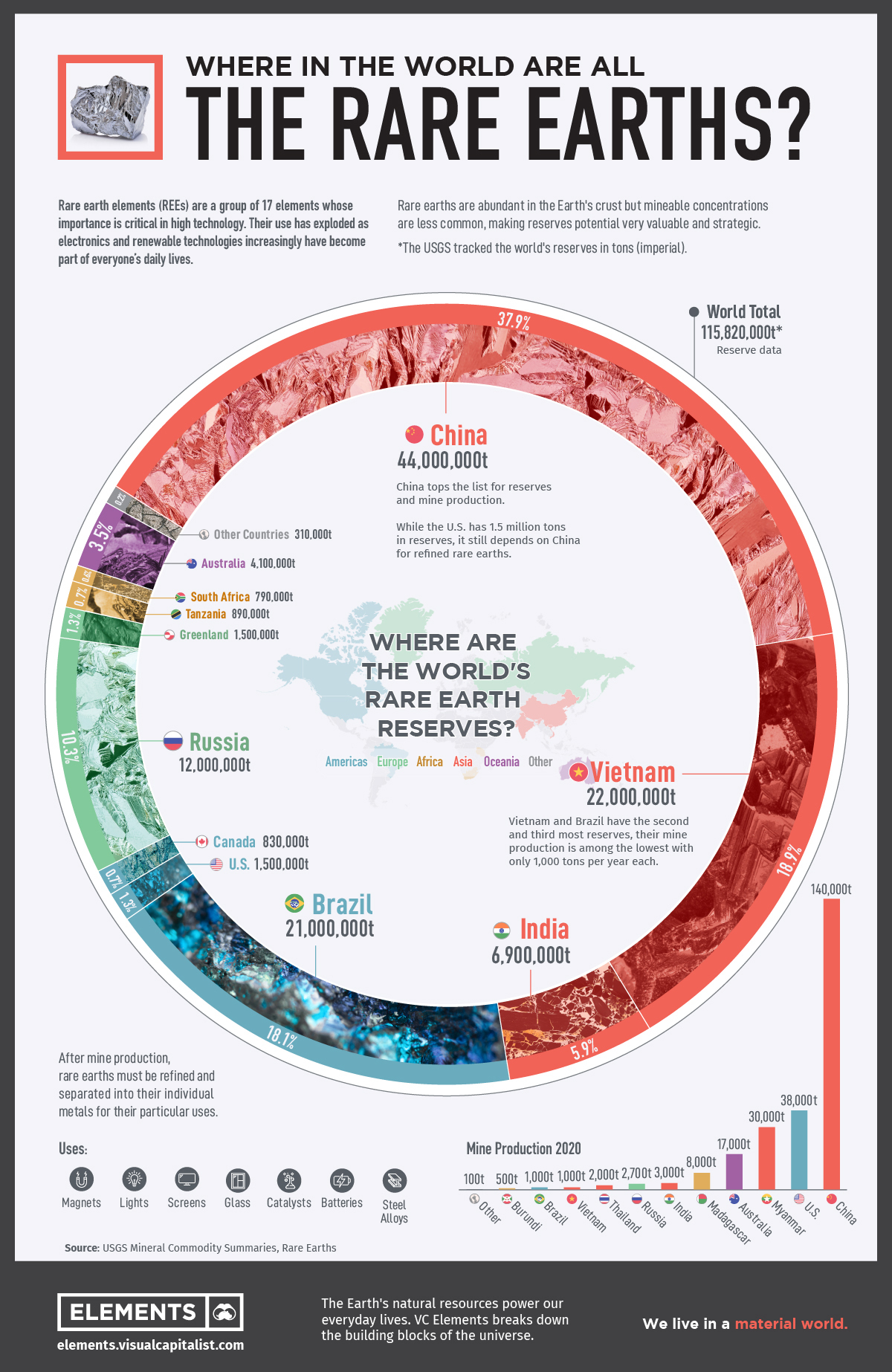

First, a short primer on REEs. Rare earths, despite their name, are not particularly rare at all. They are commonly found in the earth’s crust, as U.S. President Trump’s interests express: Greenland, Ukraine, Canada . . . But China remains by far the largest miner of REEs, mining over 270,000 metric tons in 2024. This accounted for 69% of all rare earth mining production, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The United States is a distant second with 11%, and Myanmar with 8% of mined rare earths that year.

But the chokepoint is not mining. Gradually more and more mines have been developed or reopened across the globe, including in Australia, Myanmar, Vietnam, and the United States. For example, the United States mined 45,000 metric tons of rare earths in 2024, up from 41,600 in 2023. There is a single active rare earth mine in the United States, in Mountain Pass, California. That mine used to produce most of the world’s supply of REEs from the 1960s until 1995. However, after Chinese production soared and its exports poured into global markets, Mountain Pass closed in 2002, only to reopen again with government support in 2017.

Despite Mountain Pass’ sizeable production, China remains the destination for some of its rare earth concentrates, especially heavy ones. The U.S. often ships raw mineral precursors to China for processing and re-imports them as components. By now there are processing facilities in the U.S. for light rare earths, especially neodymium and praseodymium, the most common materials used to make rare earth magnets.

Despite U.S. advances, the heavy rare earths chokepoint remains. Up until 2023, there was minimal output from a refinery in Vietnam. Yet, this sole facility outside China is closed due to a tax dispute, effectively giving China a monopoly over heavy REE processing—at least for the time being.

Japan has perfected the recycling of REEs from used electronics, but that supply remains limited. In the United States, MP Materials, the owner of the Mountain Pass mine, is moving forward with a processing facility for heavy REEs. However, despite investing nearly $1 billion since 2020, the company currently cannot process heavy REEs. In prior announcements, the company aimed for its first processing runs during 2026.

Therefore, the earliest rival supply to emerge will be from Lynas Rare Earths Corp., an Australian company with a processing facility in Kuantan, Malaysia. On May 15, 2025 Lynas Malaysia announced it had commenced its first production of separated heavy rare earths, specifically dysprosium oxide (Dy). The facility is also scheduled to begin production of terbium (Tb) in June 2025.

Dysprosium and terbium are especially critical components in the manufacturing of high-performance rare earth magnets that can operate in high temperatures, with uses in all types of advanced electronic equipment, including micro-capacitors. Since the demand for such applications is increasing rapidly, even with rival supply, Chinese dominance will remain for years to come.

Consequently, a point of failure will remain in the supply chain for rare earth magnet production outside of China. This highlights another important facet of the REE value chain: China produces more than 90 percent of permanent REE magnets, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. One possibility is therefore that Beijing could halt the export of heavy REE oxides, only to further Chinese dominance in global REE magnet production.

Currently, industry insiders outside of China expect export shortages to emerge during the summer if no or very few licenses are issued. A Reuters report in mid-May 2025 affirmed that China was already issuing export permits for magnets containing medium and heavy rare earths. This included licenses for at least four magnet producers, including suppliers to Volkswagen, the German carmaker. Volkswagen had reportedly lobbied Beijing for help on this.

The permits issued so far seem only to be for suppliers shipping to customers in Europe and Vietnam. Under the terms of the 90-day de-escalation of the U.S.-China trade war agreed to in Geneva, China said it would suspend or cancel its non-tariff countermeasures imposed on the United States since April 2. Some analyses contend that removing restrictions on the seven heavy REEs was a priority for U.S. negotiators.

Nonetheless, neither side has mentioned when REEs will begin flowing to the United States. The permitting system China has implemented to control the export of rare earths, which applies to all countries, will be retained. However, it might become easier for U.S. buyers to win approvals. Elon Musk has reportedly said that Tesla had already been in talks with Beijing over licenses for its Optimus robots.

This only serves to drive home how pronounced the heavy REE choke point is now that Beijing has implemented an export licensing system. It gives China control over the supply chains of virtually every high-tech product on earth with Western industrialized nations uniquely vulnerable.

Although new supply is slated to come on stream during 2025 and 2026 in Malaysia and the United States, it will be insufficient to meet global demand. Even further off are mines and processing facilities in regions coveted by U.S. President Trump, such as Greenland and Ukraine. Ukraine is a case in point. It will take years to develop mines and refineries there, with the average REE facility requiring 18 years to become operational.

After all, rare earths are not particularly rare, but separating them is devilishly challenging. Different REEs are merely fractions of an angstrom apart in diameter, making it very difficult to separate using physical means. Tellingly, dysprosium, infamous for its elusive presence, is named after the Greek “dysprositos,” meaning “hard to get.”

As rival facilities in Malaysia and the U.S. slowly come online, Beijing’s licensing system will nonetheless tighten its hold on global supply. A prolonged phase of uncertainty awaits while the choke point remains—and with it, a reminder that in modern industrial competition, access may matter far more than abundance.