Commemorating the 40th anniversary message to “Compatriots in Taiwan” earlier this year, President Xi Jinping of China offered a five-point proposal for a “peaceful unification” with Taiwan, but also made no promise to renounce the use of force.

In the “Grand Plan” of China, however, the Taiwan issue is simply one step in Beijing’s larger strategic objective of pushing the US and its influence out of the Indo-Pacific region. This strategic objective cannot be achieved without the support of other objectives, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and establishing control over the East and South China Seas. Each of these objectives must be understood within the regional balance of power through the Washington-led “democratic alliance” with Australia, Japan, and India, referred to as the Quad, as well as its activities in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

China’s main priority begins with the Communist Party of China (CPC) and its very legitimacy to rule. Because China’s strategic objectives are predicated on this legitimacy, the CPC must provide economic and social stability for its citizens, which cannot be achieved without an uninterrupted supply of energy resources that can not only deliver economic growth but also sustain military operations if and when needed. It is no surprise that given China’s current economic challenges, Beijing has called for “six stabilities.”

A Matter of National Identity

China’s primary objectives of protecting sovereignty claims and defending its territorial integrity begin with Taiwan as part of its national identity. For China, Taiwan is not merely a runaway province, it is a focal point in what is often called the first island chain, a series of strategic archipelagos that would allow China to project power out to the Western Pacific and to the second island chain. This is generally referred to as China’s Anti-Access/Area Denial strategy.

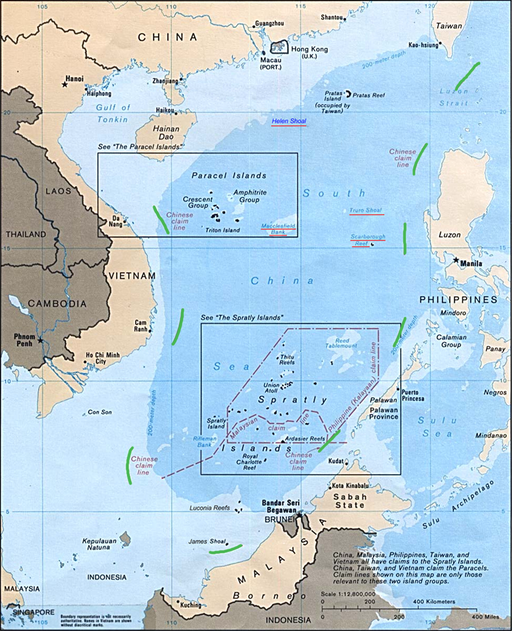

Hence, the Chinese establishment of its Air Defense Identification Zone in the East China Sea and the island-reclamation followed by military buildup in the Spratly and Paracel Islands in the South China Sea—as well as the use of a maritime militia—are not only meant to claim de facto rights to the resources within the nine-dash-line, they are tactical steps toward employing coercive diplomacy with its neighbors, and establishing operational control over the region in its move toward unification with Taiwan. Diplomatically, China is also working to “peel” away those countries that currently recognize Taiwan.

A separate but related issue is that China believes it still has some unfinished business with Japan—both with respect to the Senkaku (Diaoyu in Chinese) islands in the East China Sea—as well as in the broader historical context of national humiliation. It is likely no accident that China’s first indigenously built aircraft carrier has been called “Shandong”–a colonial province that was ceded to Japan after World War I.

The Enablers of Cultural Rejuvenation

The key enabler that has allowed Beijing to project its power has been China’s explosive economic growth. As it cools, however, major programs such as the BRI will be critical to any future projection of China’s power. As envisioned, the purpose of the BRI is to “promote regional economic cooperation, strengthen exchanges and mutual learning between different civilizations, and promote world peace and development.” However, there are other motivations not likely to be mentioned in official Chinese literature.

First, China wants to decrease dependence on its domestic infrastructure investment and begin moving investments outward to address capacity overhang within China. A key instrument of this investment transfer comes with the Chinese system of “state capitalism.”

Second, China wants to internationalize the use of its currency along the BRI. Making the renminbi a global currency had been one of the highest economic priorities of Beijing’s Grand Plan.

Third, China seeks to secure its energy resources through new pipelines in Central Asia, Russia, and South and Southeast Asia’s deep-water ports. For some years, the Beijing leadership has been concerned about its “Malacca Dilemma.” In 2003, President Hu Jintao declared that “certain major powers” may control the strait and China needed to adopt “new strategies to mitigate the perceived vulnerability.” Initiatives under the BRI—such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor to Xinjiang, the Kyaukpyu pipeline in Myanmar that runs to Yunnan, and the ongoing discussions for the proposed Kra Canal in Thailand—are of vital interest to China because they would provide alternative routes for energy resources from the Middle East directly to China that bypass the Malacca Strait.

Global Response Led by Washington

As Beijing’s intentions become clear, the continuing tensions have revived the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with Australia, India, Japan, and the US. Each of these Quad members has its own economic and geostrategic concerns over balancing China’s expanding power and influence with a host of counter-strategies; they are hardly a “containment policy” but collectively a range of constraint strategies. President Trump has, for example, signed into law the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act—a belated expression of America’s commitment to the security and stability of the Indo-Pacific region.

The United States Senate has also passed the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act to reform and improve overseas private investment to help developing countries build ports and infrastructure. It is also aimed at countering China’s influence and assisting BRI countries with alternatives to what has generally been called China’s “debt trap” diplomacy.

Viewed in the context of history, China’s rise has been nothing short of meteoric. China now seeks to create a new set of global norms, while overturning the existing norms that China claims it had no role in creating. That may be true, but China should remember that the existing international norms have also played a critical role in raising China to where it is today.

Whatever claims China has made to a “Peaceful Rise,” it is clear that “peaceful” is ringing somewhat hollow. Yet, American policies must not embark on a fool’s errand to “contain China,” which would be a historic blunder. Rather, the United States should continue to engage allies and friends to maintain a consistent and persistent presence—irrespective of the administration in place—as an expression of its unity and commitment to security, peace, and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.

In addition, the United States and its allies should apply a unified front in pressuring China and engaging Beijing to respect global norms in areas such as trade regimes, technology transfers, and intellectual property theft.

In the broader scheme of things, China should measure its ideological priorities against its costs. If and when China and Taiwan unite, it will be based upon a mutual amity and belief that it is in the interest of all Chinese people to do so—not through coercion and aggression. Beijing cannot bend history to its will.

This is an extended version of the article originally published in the South China Morning Post on Wednesday, 23 January, 2019.