There is no winner in a trade war, because sabotaging trade hurts both sides. “Killing 1,000 enemies while losing 800 of one’s own” — a Chinese saying for a scenario in which the cost does not justify the gain — is applicable in this case.

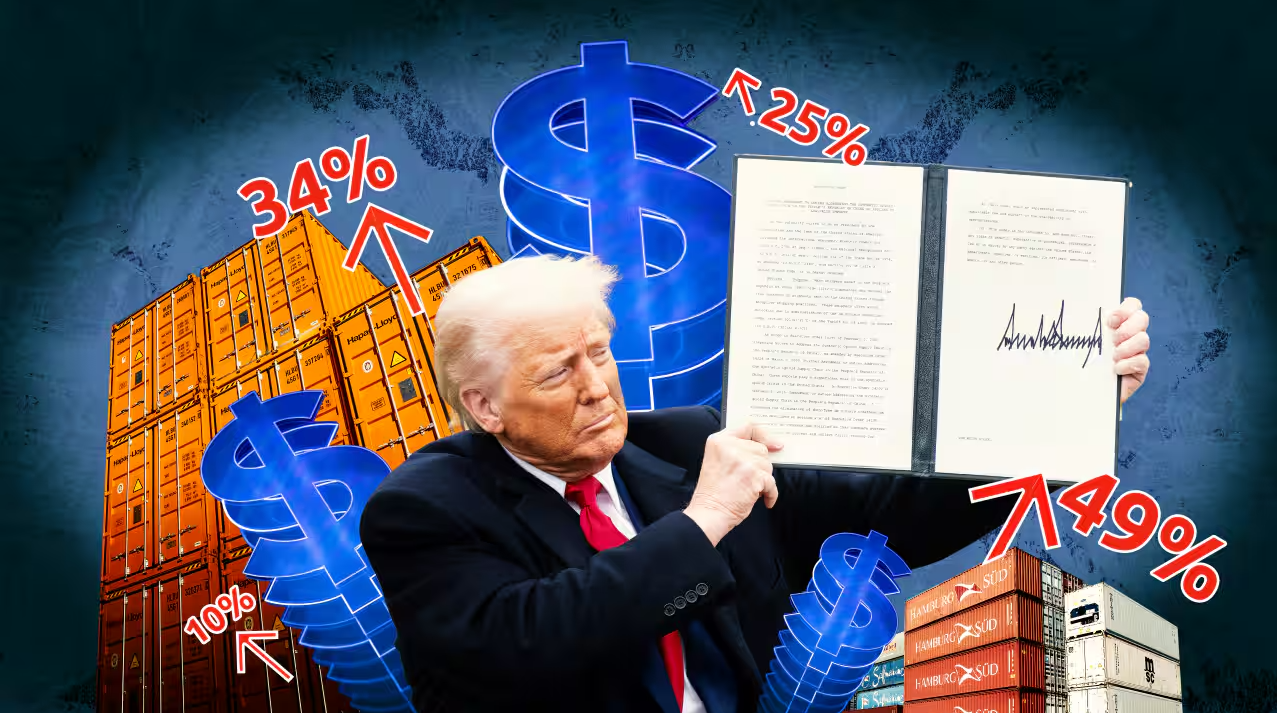

Donald Trump’s tariff war can be traced back to the trade war he launched against China during his first term in office. At the time, he accused China of unfair competition, citing its tremendous surplus in trade with the United States. He asked China to buy more and imposed tariffs of 20 to 25 percent on Chinese exports to the U.S. However, worrying that China’s buying of such tech products as advanced semiconductor chips from America could help it upgrade its “Made in China” effort more rapidly, the U.S. government moved to restrict export of tech products to China.

American tech products are prohibited from export to China, while ordinary Americans need inexpensive but quality consumer goods made in China. The trade imbalance is artificial, so it cannot be corrected. The Trump administration wants China to buy more U.S. agricultural and energy products, yet the U.S. must compete with a great number countries that export energy and farm products, so it has few advantages. It is thus fair to say that distorted U.S. trade policy has caused the serious imbalance in trade with China.

After being elected U.S. president in 2020, Joe Biden didn’t change Trump’s tariffs policy. Instead, he preserved the additional tariffs Trump had imposed, because containing China’s development had become a consensus between the Republican and Democratic parties — about the only thing they agreed upon. Trump is now escalating the trade war in his second term and has come up with a notion called “reciprocal tariffs.”

This is a complete Trump invention. There has never been such a concept in the realm of international trade, nor has any country applied tariffs on such a pretext. The way of calculating “reciprocal tariffs” is arbitrary, too, and nobody understands the reasoning. They divide the other side’s overall exports to the U.S. by its trade surplus, then arrive at a tariff rate by dividing that percentage by 2. Under this method of calculation, countries that don’t trade much with the U.S. but have sizable trade surpluses get hit with reciprocal tariffs much higher than those for China.

Facing U.S. bullying, China resolutely took retaliatory measures, after which the U.S. escalated further. U.S. tariffs on Chinese products have surpassed 145 percent, and China has hiked tariffs on U.S. exports to more than 125 percent. This alone would have cut off trade between the two countries in the past, because the cost of tariffs has far surpassed commodity prices in their respective home currencies.

We live in a time of economic globalization, and even the U.S. now engages in counter-globalization, but supply chains in a global economy cannot be cut off immediately. So U.S. financial markets have shown dramatic reactions after the government began to impose reciprocal tariffs. All international investors predict the U.S. tariff war will result in a U.S. economic recession and out-of-control inflation. Therefore, they have begun to withdraw from U.S. markets, nearly causing a major financial crisis.

The Trump administration then suspended reciprocal tariffs on all its trading partners except China. But even as it retained the tariffs against China, it exempted such products as electronics (smartphones, computers, etc.) made in China, because a considerable part of them are made by American companies, including Apple, Dell and HP.

Calm has yet to be restored in U.S. markets, and many executives of major U.S. transnational corporations and economists have issued open letters to Trump, explaining the damage the tariff war is inflicting on the U.S. economy and expressing hope that he would step back from the brink. Trump, via social media and through the White House spokeswoman, has repeatedly indicated that he would start negotiations with China soon and that the tariffs were indeed set too high. This shows that U.S. markets have already smelled a crisis. Capricious as he is, Trump has been forced to adjust his trade policy according to market expectations.

There is no winner in a trade war, because sabotaging trade hurts both sides. “Killing 1,000 enemies while losing 800 of one’s own” is a Chinese saying for a scenario in which the cost does not justify the gain. A trade war is a typical example of that scenario. However, in recent years, some U.S. political elites worry that the U.S. could lose out in the competition with China, so they don’t hesitate to engage in self-damaging advocacy. They believe anything is worth doing so long as it undermines China’s progress, even things that would hurt the U.S. badly. This way of thinking is close to insane, as following that course can only end up destroying the U.S. and won’t impede China’s steady progress and accomplishments of national rejuvenation.

The gigantic trade volume between China and the U.S. is to a great extent the outcome of some big multinationals having built a complex set of supply chains across national borders over recent decades. Once a trade war breaks those supply chains, Chinese manufacturers will suffer significant losses; yet U.S. downstream manufacturers, retail businesses and consumers may suffer even more.

Relationships such as supply chains take decades to build. Chinese supply chains are built on complete infrastructure, efficient government support, numerous supporting industrial enterprises and countless technical workers, engineers and sophisticated logistics systems. The U.S. won’t find such supply chains elsewhere in 20 years, if it wants to decouple from China. But can the U.S. afford to expend the time?