Much has been written in the overseas China studies community about the important roles that Wang Huning and Liu He play in Xi Jinping’s leadership. Wang (1955), one of the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee (the supreme decision-making body in the country), has been a key strategist in assisting Xi on both the domestic development and foreign policy fronts. Liu (1952), vice premier and a Politburo member, has been responsible for two challenging areas: China’s financial affairs and economic relations with the United States.

Less noted but profoundly consequential is that the ascendance of Wang and Liu, two scholar-officials (xuezhexing guanyuan) from think tanks, to the apex of power may have paved a new and more regular channel for political elite recruitment within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Instead of climbing the conventional ladder of elite promotion through municipal and provincial leadership, Wang and Liu both primarily advanced their professional and political careers through academic research and think tank work. Neither ever served in local administrations.

Wang served as a professor and dean of Fudan University Law School in Shanghai in the early 1990s before moving to Beijing, where he worked consecutively over 25 years as division head, deputy director, and director of the Central Policy Research Office of the CCP Central Committee (CC), a prominent Party think tank. Liu studied and taught economics at Renmin University early in his career. Beginning in the late 1980s, he worked for almost 20 years as a scholar and administrator in various government think tanks such as the Research Office of the Industrial Policy and Long-Term Planning Department in the State Planning Commission, the State Information Center, and the Development Research Center of the State Council.

Although this route of elite recruitment from official think tanks is still in its nascent stages, Wang and Liu are by no means isolated examples. To a certain extent, the effort to recruit and promote scholar-officials from think tanks is already advancing at various levels of leadership. A significant portion of members of the 19th Central Committee previously served — or even currently serve — as analysts and administrators at some of the in-house Party or government think tanks. They have emerged as a distinct elite group in the Party-state leadership of present-day China.

It is unclear at this point whether Wang and Liu will retain or obtain membership, respectively, on the new Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) this fall. Given the leadership lineup of other prominent leaders advancing their careers from official think tanks, one can reasonably expect that this elite group will be well represented in the CC, the Politburo, and perhaps even in the PSC in Xi’s third term.

The role of Chinese think tanks from a historical perspective

For people in China, the term “think tank” (zhiku or sixiangku) is somewhat novel, even though the concept and idea are by no means new. As a Chinese analyst observes, “Though many believe that modern think-tanks were born in the United States, China does have a long-standing partnership between intellectuals and policymakers that can be dated back to ancient dynasties.” One could reasonably argue that think tanks have played an important role in Chinese society since the time of Confucius, when “gentry-scholars” (shidafu) were essential figures in civic administration, providing emperors with policy recommendations and educating the public.

However, during much of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) history, and especially during its first four decades, the role and influence of think tanks largely depended on the preferences and characteristics of the country’s paramount leader. Mao Zedong did not value expert knowledge or the public policy process; thus, he disregarded rationality in state affairs and held intellectuals in low esteem. Major decisions during the Mao era were largely made by Mao alone, including launching the Cultural Revolution, shifting China’s national defense industry to the so-called interior “third front,” and pursuing rapprochement with the United States in the early 1970s.

Although Deng Xiaoping greatly improved the economic and sociopolitical status of intellectuals during his reign, he hardly consulted think tanks when making decisions. Deng’s most significant decisions — opening China to foreign investment, normalizing Sino- U.S. relations to contain the former Soviet Union, and establishing Special Economic Zones in southern China and then in Shanghai’s new Pudong District — have all been attributed to his own visionary thinking and political courage.

Jiang Zemin, Zhu Rongji, and their generation of technocratic leaders paid more attention to the role of think tanks than their predecessors. As a top leader, Jiang Zemin often received advice from scholars at Shanghai-based institutions such as Fudan University, the East China University of Political Science and Law, and the Shanghai Institute of International Studies. These think tanks provided much-needed expert analysis on important issues, such as China’s accession to the WTO and other economic and foreign policy initiatives.

Following in Jiang’s footsteps, Hu Jintao turned the Central Party School (CPS) into a prominent think tank when he served as its president in the late 1990s. The CPS has long functioned as a leading research center on China’s domestic reform and international relations. Both Zheng Bijian, former vice-president of the CPS, and Wang Jisi, then-director of the Institute of International Strategic Studies of the CPS, played crucial roles in the development of Hu’s theory of “China’s peaceful rise.”

The development of think tanks as national strategy in the Xi era

Under the leadership of Xi Jinping, think tank development has become a government-sponsored national strategy (guojia zhanlue). Xi’s elevation of think tank development as a national strategy sparked “think tank fever,” an unprecedentedly high-profile discussion in China on the role of think tanks. Many institutions across the country — including those within the Party apparatus, government ministries, the military establishment, local administrations, universities, research institutions, business enterprises, social organizations, and media outlets — have ridden the wave following Xi’s pronouncement by establishing so-called “new types of think tanks with Chinese characteristics.”

According to Li Wei, former director of the Development Research Center of the State Council, China has approximately 2,000 think tanks, 90 percent of which are run by the Party-state. Among the Party-state-run think tanks, about 40 are situated at the national level (e.g., the Central Policy Research Office and the CPS), about 160 are situated under provincial level administrations (e.g., the provincial Party committee research offices and the provincial academies of social sciences), and 1,300 are operated at the prefecture and city level (e.g., the municipal government research offices and municipal Party schools). Altogether, these think tanks employ approximately 35,000 researchers and 270,000 supporting staff.

In December 2015, the Chinese government announced the first group of 25 high-level (gaoduan) think tanks, covering politics, economics, ideology, science and technology, military, law, and international affairs. Like their counterparts in many other countries, these prominent Chinese think tanks serve multiple functions: gathering intelligence, analyzing events, assessing risks, drafting laws and regulations, and recommending and evaluating policy. Some can access decision-makers through policy reports, public opinion polls, roundtable briefings, and other channels.

According to Li Yang, former vice president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), the CASS maintains a direct channel through which it can submit reports for circulation among the roughly 40 highest-ranking leaders in the country — presumably members of the Politburo, Secretariat, and the executive committee of the State Council.

Some of the major policy initiatives associated with a top leader can also be traced back to discussions that occurred at specific research institutions or in conversation with prominent scholar-officials at a think tank. It is widely believed that Jin Liqun, an internationally renowned Chinese financial technocrat, recommended Xi Jinping to found the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), of which Jin currently serves as president.

More often, prominent Chinese think tanks are directed by top leaders to conduct further studies on certain policy initiatives. For example, after Xi Jinping launched the “One Belt One Road Initiative” (later the Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI) in Central Asia in September 2013, ten think tanks were ordered to examine various aspects of this undertaking. The following year, China established nine new think tanks focusing exclusively on Central Asia.

These new developments seem to contradict Xi’s politically conservative approach to governance. The tightening of ideological oversight and political control over intellectual discourse at Chinese universities, NGOs, and on social media has caused much concern both at home and abroad. Chinese liberal intellectuals have long been critical of the crackdown on open discussion of the “seven subversive currents,” including constitutional democracy, human rights, civil society, and media freedom. As a Chinese critic observed, in general, Chinese scholars in think tanks are required to “endorse” (beishu) government policies rather than critically evaluate policy initiatives and openly express dissent.

These critics’ views are largely valid, but they should not be a reason for students of China to overlook Xi’s objectives to promote think tank scholars and the remarkable rise of academic-turned-politicians in the Party leadership. From Xi’s perspective, modern governance — including public policy in finance, trade, investment, taxation, budget, technology, the environment, and energy — requires special knowledge and expertise. China’s economic rise on the world stage, integration with global financial institutions, ambition to catch up to more advanced countries in science and technology, and the need to improve the country’s international image all require that scholars in think tanks assume a larger role in policymaking.

In April 2016, Xi proclaimed that China should adopt the “revolving door” (xuanzhuanmen) mechanism prevalent among think tanks in many foreign countries, whereby political and intellectual elites move fluidly between positions in think tanks and the government. More recently, in May 2021, Xi emphasized that China should “strengthen the functions of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Engineering in being national high-level think tanks, enable strategic scientists to play important roles, and actively carry out expert consultation and evaluation to serve national decision-making.”

China’s high-level official think tanks to watch

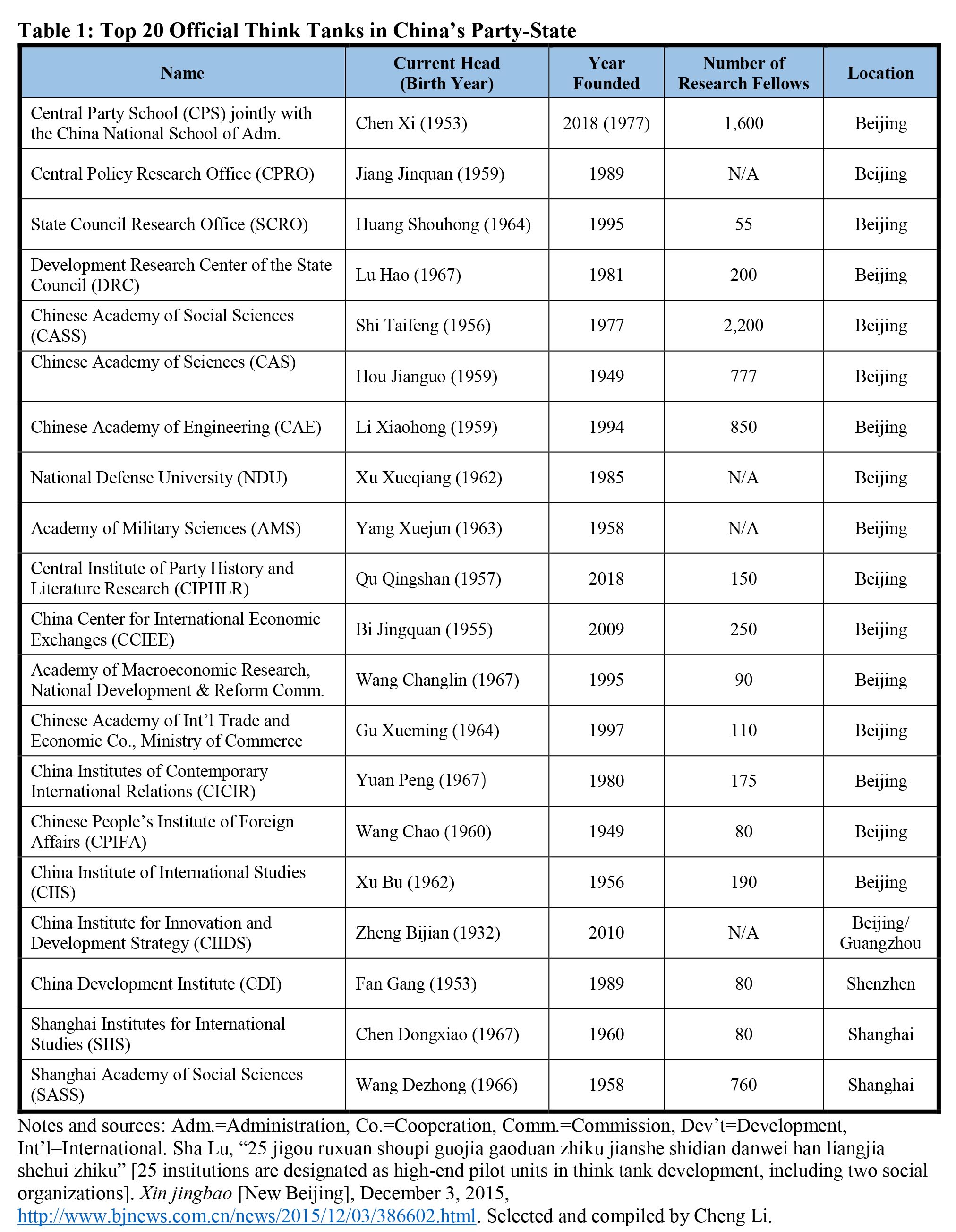

Chinese think tanks are a diverse lot. Even the high-level think tanks run by the Party-state differ significantly in terms of size, research capacity, thematic focus, bureaucratic affiliation, and ability to access top leadership. Table 1 lists the top 20 official think tanks in China’s Party-state, which is based partly on my long-standing observation of Chinese think tanks and their importance in policy influence and impact. This list, of course, should not be seen as all-inclusive.

More than two-thirds (14 of 20) of the think tanks on the list were also included among the first group of 25 high-level think tanks designated by the Chinese government in December 2015. That list of 25 high-level think tanks includes six university-based think tanks excluded by this study. Surprisingly, the 2015 list made by the Chinese authorities did not include some of the most influential official think tanks, such as the Central Policy Research Office and the State Council Research Office, which this analysis includes.

The other four official think tanks listed in Table 1 but not on the 2015 list are the Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs (CPIFA); the China Institute of International Studies (CIIS), which the Ministry of Foreign Affairs directly administers; the China Institute for Innovation and Development Strategy; and the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (SIIS). These four think tanks are included here largely because of their active international outreach and exchanges in recent years, which are increasingly considered the primary channel for China’s “second track diplomacy” (ergui waijiao).

The prominent think tanks in Table 1 were established during different periods. The Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the CPIFA were inaugurated as early as 1949, the same year the PRC was founded. More than half of them (13 of 20) were established in the reform era. The Central Party School was merged with the China National School of Administration in 2018. The inauguration of the CPS can be traced back to the period following the founding of the CCP in the 1920s, but the CPS gained prominence as a think tank largely after the Cultural Revolution in 1977, when then CPS executive vice president Hu Yaobang oversaw the school. In 2018, the CCP leadership also merged the Central Party History Research Office, the Central Documentation Research Office, and Central Compilation and Translation Bureau into the Central Institute of Party History and Literature Research.

Most of these high-level think tanks are in Beijing. The largest think tank in the PRC is, of course, the CASS, which consists of 31 research institutes and 45 research centers and boasts 4,200 employees, including 2,200 research fellows. Because of its robust and comprehensive research capacity, the CASS has been the country’s leading think tank in virtually all areas, especially in socioeconomic and demographic studies.

The Central Policy Research Office (CPRO) is a small think tank, and its total number of staff is unclear (with probably only two or three dozen scholar-officials). But due to its proximity to the top leadership and its key role in policy formation, CPRO is arguably the most important official think tank for China analysts to watch. While it was officially named and founded after the Tiananmen incident in 1989, it was a merger of two prominent think tanks at the time, namely, the Central Research Office of Political System Reform, which was previously headed by Zhao Ziyang’s political secretary Bao Tong, and the Rural Development Research Center of the State Council’s Development Institute run by distinguished economist Du Runsheng (and earlier by Wang Qishan).

Many current heads of these top 20 official think tanks serve as members of the 19th CC. They include one Politburo member, Chen Xi (1953), and eight full members, Huang Shouhong (1964), Lu Hao (1967), Shi Taifeng (1956), Hou Jianguo (1959), Li Xiaohong (1959), Yang Xuejun (1963), Qu Qingshan (1957), and Bi Jingquan (1955). Central Policy Research Office Director Jiang Jinquan (1959) is a member of the 19th Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, and he will likely be promoted to serve on the Secretariat or even the Politburo at the Party Congress this month. National Defense University President Xu Xueqiang (1962) will likely obtain a full membership on the 20th CC.

Some of the deputies in these top 20 think tanks are also members of the 19th CC or will likely enter the 20th CC as first-timers. Members of the 19th CC include CPS Executive Vice President Xie Chuntao (1963) and Chinese Academy of Sciences Executive Vice President Yin Hejun (1963). Possible first-timers include Central Policy Research Office Deputy Director Tian Peiyan (1961), CASS Vice President Gao Xiang (1963), and Central Institute of Party History and Literature Research Vice President Chai Fangguo (1963).

Altogether, these scholar-officials from China’s high-level official think tanks not only hold important posts in the Party’s power structure but also have significant influence as the drafters and designers of ideological indoctrination and policy blueprints for the top leadership, especially in preparing amendments to the CCP Constitution and speech for Xi Jinping at the 20th Party Congress. The following article will address this topic in detail.