For the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), any economic and financial issue usually takes a back seat to political concerns, including national security and sociopolitical stability in the country. Paradoxically, however, at a time when the world’s second largest economy has increasingly integrated into international financial markets, a major misstep on this front can potentially undermine China’s national security and lead to broad sociopolitical upheavals.

The intriguingly uncertain––but critically important––prospects of the international financial landscape have long alerted Beijing and driven Chinese decision makers to mitigate possible systemic financial risks. What arguably can be seen as a blessing for China is that its emergence as an economic powerhouse on the world stage has been accompanied by the rise to prominence of some seasoned financial technocrats or self-taught experts.

Financial technocrats in China’s national and provincial leadership

Executive Vice Premier Han Zheng (1954), Vice Premier Liu He (1952), and Vice President Wang Qishan (1948) have developed a reputation in China and abroad as leaders with strong backgrounds in financial affairs. They are among the most influential aides to Xi Jinping, especially on economic and financial matters. In the next tier, State Councilor Xiao Jie (1957), Minister of the National Development and Reform Commission He Lifeng (1955), Governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) Yi Gang (1958), Chair of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission Guo Shuqing (1956), and Executive Deputy Director of the General Office of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission Han Wenxiu (1963) have spent decades of their professional and political careers handling the financial administration of the country.

Some will likely retire next year, such as Wang Qishan. Others are expected to stay in their top financial leadership positions, as was the case with Zhou Xiaochuan (1948), whose appointment did not follow the term limits and mandatory retirement age. Zhou served as governor of the PBOC for 16 years (2002-2018). Still, others will be promoted further and play an even more important role after the 20th Party Congress. For Xi Jinping, this arrangement may help provide some assurance both at home and abroad about continuity and stability in this pivotal area.

Meanwhile, a group of younger (6G and especially 7G) financial technocrats with solid professional training and global financial administrative experience will likely enter the new CCP Central Committee this fall for the first time. They currently serve as vice provincial-ministerial level leaders. Many of them are among the first group of leaders officially designated as a “provincial vice governor in charge of financial affairs” (jinrong fu shengzhang), a recently adopted elite recruitment mechanism aiming to address the financial challenges confronting China’s 31 province-level governments.

The growing importance of finance in China’s development

The rising influence of financial technocrats in the Chinese leadership reflects the growing importance of finance in the country’s development. From the perspective of the CCP leadership, financial strength is “a core area of competitiveness of the country.” China’s financial sector has witnessed remarkable growth during the reform era. The added value of China’s financial industry has increased from 7.65 billion yuan in 1978 to 8.4 trillion yuan in 2020, and its share of GDP has increased from 2.1 percent to 8.2 percent in the same period.

Also in 2020, almost two decades after China’s accession to the WTO, the loan balance of Chinese financial institutions increased to 178.4 trillion yuan, 16 times greater than in 2001. In 2020, there were a total of 4,140 listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, about four times the number of listings in 2001.

The growth of financial institutions is also phenomenally high. In 2020, there were more than 4,600 banking institutions, 239 insurance institutions, 129 securities companies, around 24,500 private equity fund companies, and 136 public fund management companies. By September 2021, the total size of China’s public funds reached 23.9 trillion yuan, an “explosive increase” of 295 times compared to only 80.9 billion yuan in 2001.

Over the past decade, some Chinese state banks have risen to become gigantic global financial institutions. Among the 10 largest banks in the world in terms of capitalization in 2021, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank, and Agricultural Bank of China occupied the top three seats. Bank of China was ranked No. 5.

At the same time, especially at the provincial and municipal level, large state-owned enterprises and real estate companies have defaulted one after another, and the resolution of hidden debts and the disposal of high-risk financial institutions have all tested the ability and responsibility of local governments to respond. China’s provincial and municipal economies are large entities. Guangdong’s GDP, for example, exceeds Russia’s GDP; and even more importantly, Guangdong’s financial activities are even more deeply integrated into the international financial system than those of Russia. Unsurprisingly, there have been heated discussions in China about how U.S.-NATO financial sanctions against Russia reveal the challenges that the Chinese financial industry will have to address now and in the future.

Beijing’s concerns regarding external and internal financial risks

The financial challenges that China has confronted can be attributed to both external and internal circumstances, which are intimately intertwined. For the international financial environment, a combination of factors such as China’s heavy weight in global trade, its relatively less developed financial services, comparatively weak currency, vulnerability to cross-border capital flows, and ongoing U.S. sanctions and restrictions against Chinese financial firms have all placed China in a disadvantageous or difficult position.

In terms of domestic circumstances, the list of challenges is also long and multi-faceted, including the enduring problems of shadow banking, local debts, and real estate bubbles; poorly performing Chinese stock markets and extraordinary volatility over the past two years; and the growing imperative to effectively prevent risks relating to financial network technology and information security in the AI era. Recent events, such as the crisis of public confidence about the prospects for Hong Kong as a vibrant global financial hub and the pandemic lockdown of Shanghai, have reaffirmed the strong linkage between security and politics on one hand and economic and financial matters on the other.

In November 2021, the Politburo reviewed and passed “The National Security Strategy (2021-2025)” in which the Party leadership asserted that “political security comes first.” At the same time, the strategy also emphasizes that the most crucial and urgent task for the country is to “consolidate the bottom line of security against systemic financial risks” and “strengthen the security protection of overseas interests.”

This recognition on the part of the Chinese leadership is not new. Virtually every year over the past decade, Xi Jinping addressed the financial risks and potential crises that his administration confronted. In January 2016, Xi stated that the continuous occurrence of terrible incidents in the stock market and internet finance in recent years “have repeatedly sounded the alarm.” Maintaining financial security, therefore, is “a strategic and fundamental task” related to China’s overall economic and social development. At a Politburo study session on safeguarding China’s financial security held in April 2017, Xi Jinping endorsed the expression that “if finance is vibrant and steady, so is the economy.”

While most of these publicly announced statements can be interpreted as the Chinese leadership’s reaction to the rapidly changing financial system in today’s world, some have reflected China’s more foresighted strategic moves. As early as 2013, in a speech delivered at Nazarbayev University in Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan, Xi appealed to Russia and other Central Asian countries to promote “cooperation in local currency settlement,” which he claimed “can greatly reduce the cost of circulation” and “resist financial risks.”

With both the recognition of financial challenges and the ambition to become a global financial powerhouse, the Party leadership has endeavored to foster a cluster of technically well-trained and globally minded financial experts-turned-officials in the national and provincial leadership.

“The new kid on the block”: Vice provincial governors in charge of financial affairs

Appointing financial technocrats from the banking sector to serve in the provincial government is not an entirely new phenomenon. Some prominent leaders in China’s financial industry have previous experience as provincial and municipal chiefs. Two decades ago, for example, Dai Xianglong (1944), then governor of the PBOC, was transferred to become Tianjin mayor. Almost a decade ago, Guo Shuqing, who had long worked in the financial sector, was appointed as Shandong governor, a position that he held for four years (2013-2017) before assuming his current position as chair of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission.

In 2017-2018, the Central Organization Department of the CCP launched a more systematic approach to promote bureau-and-department level financial officials to serve as vice governor or vice mayor in China’s 31 province-level administrations. Over the past four years, the number of provinces with a vice governor in charge of financial affairs has doubled –– from 10 in 2018 to 20 in May 2022. Most of them (15 out 20) are currently members of provincial Party Standing Committees. Six of them serve as an executive vice mayor or executive vice governor.

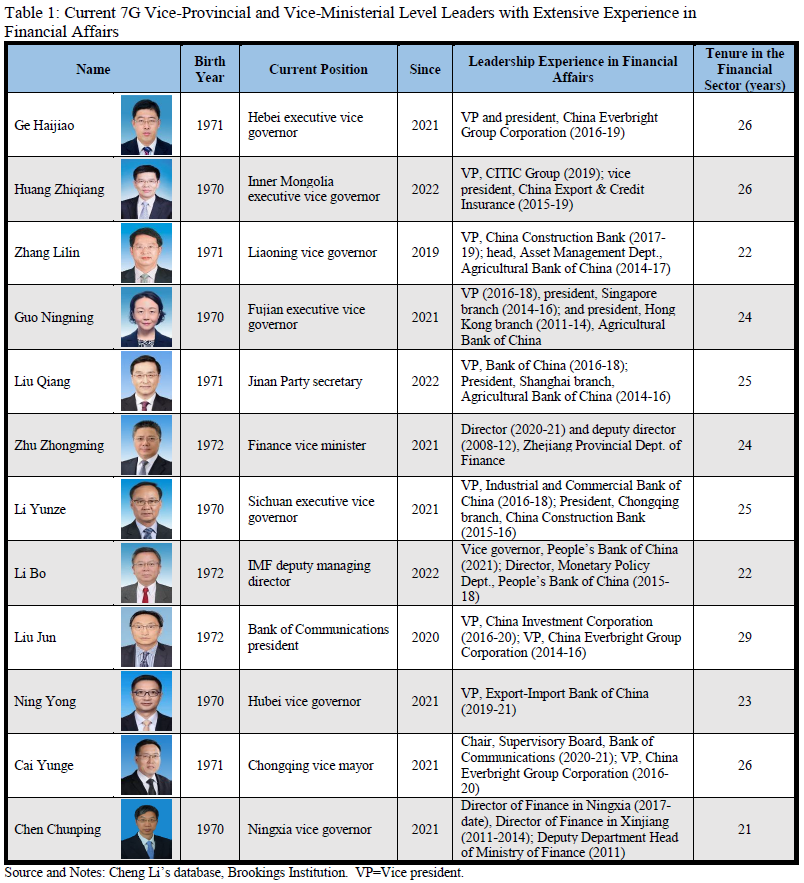

Almost all vice provincial governors in charge of financial affairs are relatively young and thus positioned well for further promotion in the years to come. Table 1 lists current 7G vice-provincial and vice-ministerial level leaders with extensive experience in financial affairs. The 7G age cohort constitutes 45 percent of this rising elite group of “vice provincial governors in charge of financial affairs.” Four of them currently serve as executive vice governors, ranked as the No. 2 leader in their respective provincial government. They are among the leading candidates for alternate membership on the 20th Central Committee this fall.

It should be noted that some financial experts-turned political leaders born in the 1960s will also be strong candidates for membership on the 20th Central Committee. They include Beijing Vice Mayor Yin Yong (1969), Tianjin Executive Vice Mayor Liu Guiping (1966), Vice Minister of Finance Liao Min (1968), Vice Chair of China Securities Regulatory Commission Fang Xinghai (1964), Liaoning Vice Governor Zhang Lilin (1971), Guangdong Vice Governor Zhang Xin (1967), Vice Governor of PBOC Chen Yulu (1966), Deputy Party Secretary of China People’s Insurance Group Zhang Tao (1963), Chair of China CITIC Group Zhu Hexin (1968), and Chair of the Agricultural Bank of China Gu Shu (1967). Some of them are seen as proteges of Vice Premier Liu He, who has overseen China’s financial sector over the past five years.

All the 7G leaders listed in the table, except for Zhang Lilin who has served in his current position since 2019, were appointed within the past two years. All of them have had more than two-decades work experience in the financial sector. In addition to these nine current vice governors in charge of financial affairs, Vice Minister of Finance Zhu Zhongming (1972) served as Hunan vice governor before being appointed to his current position in 2021. Similarly, IMF Deputy Managing Director Li Bo (1972) previously served as Chongqing vice mayor for two years (2019-2021).

What sets these younger leaders apart from proceeding generations of financial technocrats in China is that they often have received impressive educational and work credentials, including doctoral degrees in finance or economics and substantial financial leadership experience overseas. Li Bo, for example, holds a Ph.D. from Stanford University and an M.A. from Boston University, both in economics, as well as a J.D., magna cum laude, from Harvard Law School. He practiced as a lawyer for five years (1999-2004), first at the New York headquarters of the David Law Firm and then in the Hong Kong Office of the David & David Law Offices. He returned to China in 2004 to work at the PBOC, first as deputy director and director of the Department of Treaty and Law and finally as vice governor. Currently, Li is responsible for the IMF’s work on about 90 countries as well as a wide range of policy issues.

Another example is Fujian Executive Vice Governor Guo Ningning (1970), the only female provincial governor in charge of financial affairs. She served at the Bank of China for 15 years, including many years in Hong Kong and Singapore, where she headed Bank of China branches. After serving as vice president of the Agricultural Bank of China for two years, she was transferred to Fujian where she served first as vice governor and is now executive vice governor. Over the past few years, Guo received much praise for her policy initiatives in Fujian — from promoting e-commerce and e-banking, to providing accessible loans to underprivileged groups, to offering scholarships for children from low-income families. In 2021, Time magazine named her as one of the top 100 most influential future leaders in the world.

A major Chinese newspaper recently referred to this new elite group as “provincial CFOs.” Time will tell how these “new kids on the block” will respond to the many daunting economic and financial challenges at both the provincial and national levels, and whether they can derive the political guts and leadership skills that might be new to them considering their career backgrounds. Furthermore, it is also yet to be known whether their strong international financial experience changes the ways in which they respond to foreign concerns and criticism and how fault lines will be drawn between competing elite groups within the Chinese leadership.

Like any given country, the educational and occupational identities of political leaders usually have a bearing on the main objectives and other characteristics of China’s development. The growing presence of these young financial experts-turned-political leaders in the CCP reflects this new trend. One may reasonably argue that if political elites have professional expertise and interest in a certain policy area, they will strive to leave a legacy of strong leadership in that domain.