The whole world, including China, has been distressed by the troubling developments in Europe, especially the scale, scope, and devastating ramifications of the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war. As the second largest economy in the world, China has been hit badly by both the devastating impact of Russia’s horrific invasion of Ukraine on the global economy and by the potential (and actual) U.S.- and NATO-led secondary economic sanctions levied against China because of Beijing’s strong ties with Moscow.

Not surprisingly, Chinese public opinion –– and especially the outlook within elite groups, such as intellectuals, entrepreneurs, and officials –– is quite divided in terms of how China should position itself in this rapidly changing international environment. Some Chinese critics have asserted on social media that Beijing should not allow Russia to hijack China’s foreign policy. The diverse views regarding this major foreign policy issue largely stem from the fact that China’s international engagement in the reform era, including substantial educational and cultural exchanges overseas, has largely been with Western countries and especially the United States, not with Russia, as explained in the previous article in this series.

This poses a major challenge on the foreign policy front for Zhongnanhai on the eve of the 20th Party Congress as Xi Jinping seeks to achieve leadership unity and policy consensus. An understanding of the strategic dilemma that the Xi administration confronts and the development of its policy for evolving China-Russia relations carries critical importance for the outside world.

A key foreign policy dilemma for Beijing

One need not be an expert in international relations to understand that the Chinese leadership confronts a major foreign policy dilemma in its relations with Russia. China’s power on the world stage, geopolitical interests, and view of the post-Cold War world order all differ profoundly from those of Russia. China is a rising global power that has benefited greatly from post-Cold War economic globalization while Russia has been substantially weakened by the post-Cold War international order and is often seen as what President Obama described in 2014 as no more than a “regional power.”

From the perspective of the Chinese leadership, maintaining a good relationship –– or even a partnership –– with Russia, should not come at the expense of completely alienating Western countries, especially the EU, which has been the largest economic partner for China this year. It is not in the interest of China to return to what the Chinese call “bloc politics” (jituan zhengzhi), the era during which two confrontational blocs existed in the early years of the Cold War. As a scholar at a Chinese official think tank recently wrote: “The Western powers have now reunited as a result of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, and they have shown a clear strategic posture of tying China and Russia together.”

Yet Chinese leaders have claimed that NATO’s eastward expansion is the root cause of Russian aggression, and thus Beijing has not condemned it. The Chinese authorities also explicitly emphasize that China does not want to see Russia defeated by the U.S. and NATO. They believe that, following Russia’s potentially fatal loss of this war, the U.S. and its allies will focus their efforts on defeating China, the country that some in Washington perceive to be the “most formidable enemy.”

Many recent moves by the U.S. have all reinforced Beijing’s perception of this dark scenario for China. Examples include Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy, President Biden’s repeated statements that the U.S. will “protect Taiwan militarily,” the bipartisan U.S. Congress “Taiwan Policy Act 2022” that included Taiwan as “a non-NATO ally,” the “chip alliance” or “semiconductor industry alliance” aimed at containing China’s development in this crucial area of technology, and Western rhetoric about “democracy versus dictatorship” binaries in today’s world.

Under these new circumstances, the Chinese leadership has apparently moved even closer to Russia and has become more actively engaged with international groupings in which Russia is heavily involved such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO, which includes China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan). While China has not provided military weapons to Russia, as U.S. government officials have acknowledged, Beijing has not been supportive of U.S.-led economic sanctions against Russia.

Also noticeably, at the recent SCO summit in Uzbekistan, Russian President Vladimir Putin even told the media that China had “questions and concerns” about the war in Ukraine. But this should not be interpreted as meaning that China’s strategic ties with Russia are “shaky,” as some Western media have claimed. A prevailing signal of the Chinese position, as Xi Jinping stated in his meeting with Putin in Uzbekistan, is that “China and Russia are willing to provide support on issues concerning each other’s core interests.” Beijing aims to convey the message that the U.S. and European countries should not go too far to support Taiwan independence. If they do, China will show even more support for Russia.

Resurging dynamic exchanges between China and Russia

The ongoing mutually reinforced fear and animosity between China and the United States in both the regional and global security domains will likely continue in the years to come. The intriguing China-Russia relationship, especially its future trajectory, should be understood in this broader context. It is also helpful to grasp the growing multidimensional areas of engagement between Beijing and Moscow over the past decade.

Despite the absence of an “ideological glue,” in the words of the late Zbigniew Brzezinski, or mutual trust among the peoples of these two former rivals (from the 1960s to the end of the 1980s), Chinese and Russian leaders are now inclined to show solidarity to combat what they perceive to be a “formidable threat” from the U.S.-led military bloc. During Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s visit to China in March 2021 to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the “Treaty on Good-Neighborhood and Friendly Cooperation between Russia and China,” he stated that “Sino-Russian relations are now at the best level in history.” Lavrov elaborated that he and his counterpart, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, shared the opinion that Russian-Chinese foreign policy interaction remains a vital factor in global geopolitics.

Such an assessment is backed by empirical evidence from bilateral trade flows, Russia’s energy supplies to China, the growing proportion of settlements through their own currencies, and cooperation in other areas such as agriculture and aerospace. In 2021, the total bilateral trade volume between China and Russia reached $147 billion. Six months after the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war, trade between China and Russia has grown by nearly 30 percent compared with the same period last year. This year’s Sino-Russian trade is expected to exceed $170 billion, a new high.

According to Chinese customs statistics, Russia exported 8.4 million tons of crude oil to China in May, a record high, surpassing Saudi Arabia to become China’s largest crude oil supplier, an increase of about 55 percent from last year’s 5.4 million tons. Russia has remained the largest oil supplier to China in recent months. The “Power of Siberia 1” pipeline, which officially began operation in 2019, has repeatedly exceeded the contracted volume of natural gas delivered to China and is expected to reach 20 billion cubic meters this year. The “Power of Siberia 2” pipeline is currently in the contract process. According to plans, it will provide China with nearly 50 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year when completed.

Based on what Chinese Ambassador to Russia Zhang Hanhui told the media earlier this year, the proportion of RMB in bilateral trade settlements between China and Russia has increased from 3.1 percent in 2014 to 17.5 percent in 2020. This year, according to official Russian accounts, the proportion of bilateral trade settlements in RMB or rubles between China and Russia may reach 45-65 percent.

The Chinese government has also made concerted efforts to promote Sino-Russia cooperation between China’s three northeastern provinces (especially Heilongjiang) and the Russian Far East, where most of 4,300 kilometers of border lines are located. Beijing hopes that this will contribute to advancing the long-delayed “revitalization of the three northeast provinces,” especially in the areas of resources, the establishment of China’s national energy strategic reserve base, agricultural products, manufacturing, and construction projects. According to official Chinese media, the Russian Far East lacks the large amount of labor required for agricultural production, and 30 percent of the foreign labor in the region comes from China.

China-Russia space cooperation, which is widely seen as an important domain of the comprehensive strategic partnership, has reached a new stage of vigorous development in the fields of lunar and deep space exploration, manned spaceflight, satellite navigation, earth observation, and other applications. In 2021, China and Russia signed a memorandum to cooperate on the construction of an international lunar scientific research station. As the U.S.-based China Aerospace Studies Institute reported, despite China’s recent advancement in aerospace and aviation technology and R&D emphasis on engine design, China can still substantially benefit from Russian technology in this area.

Some prominent leaders in China’s aerospace and aviation industry studied in Russia. For example, Wang Changqing (1973), president of the Third Academy (China Academy of Aerospace Science and Industry Aviation Technology) under the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC), spent four years (2002-2006) in Russia, where he received his Ph.D in physics and dynamic technology at the National Research University Moscow Power Engineering Institute. The academy that Wang oversees is a high-tech scientific research and production base for flight vehicles in China.

The rapid increase in Sino-Russian educational exchanges

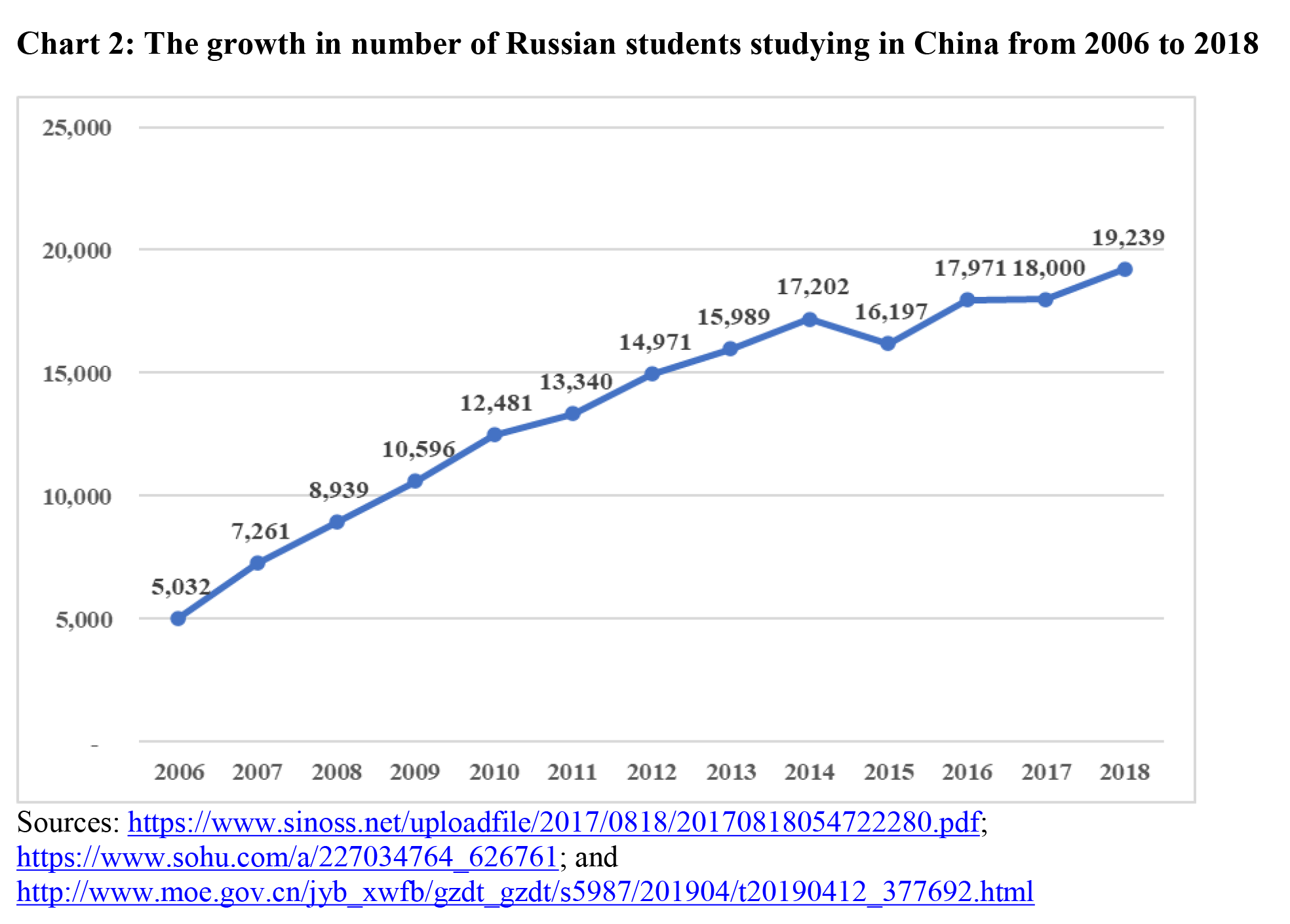

Educational exchanges between China and Russia have also witnessed rapid growth over the past two decades. In 1997, 557 Russian students were studying in China. That number increased to 7,261 in 2007, and to over 18,000 in 2017. In 2016, the two governments proposed that the total scale of bilateral study abroad would reach 100,000 in 2020. In 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Russians accounted for 8 percent of international students in China, ranking sixth in the number of foreign students in China.

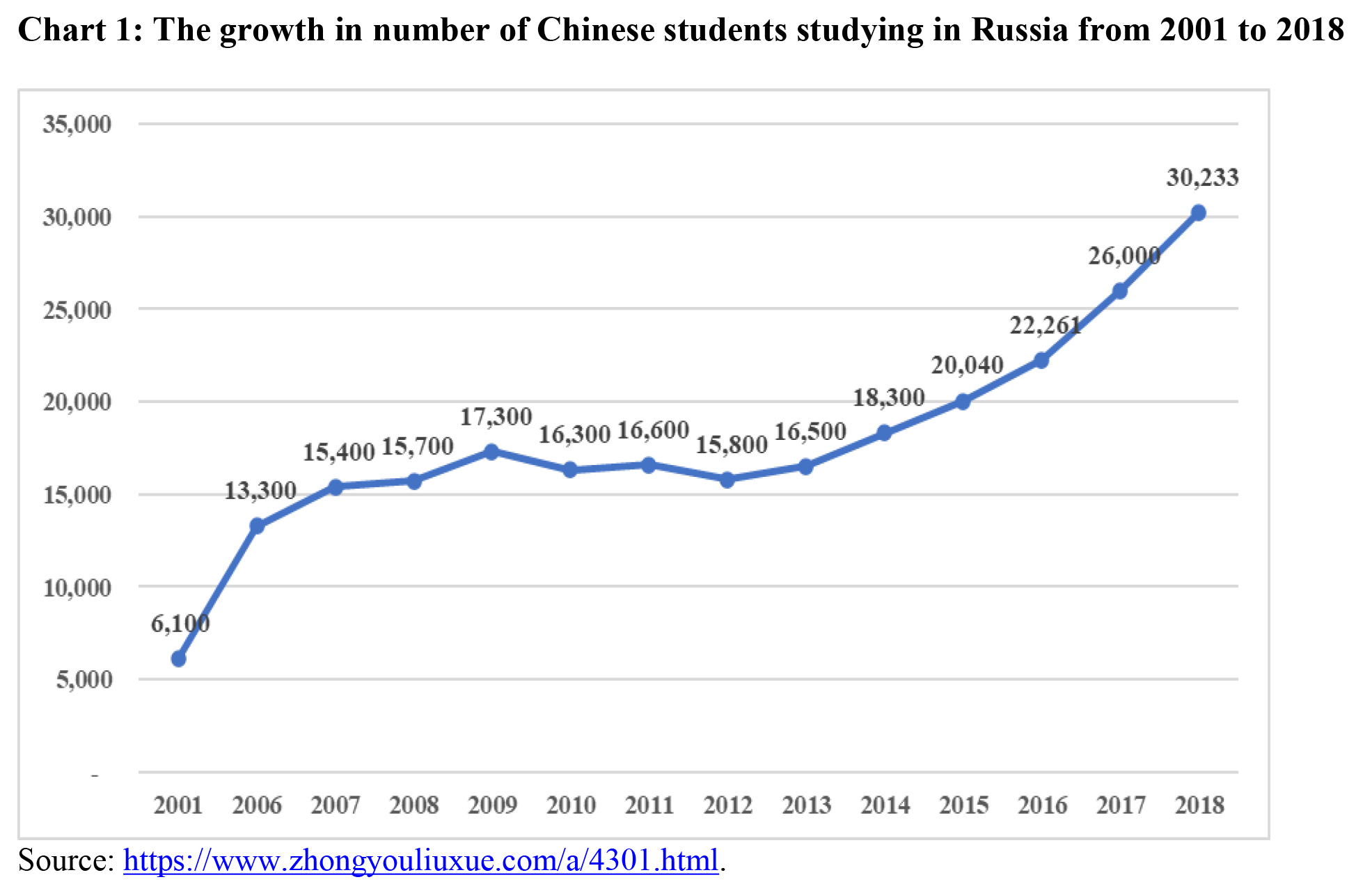

In the same year, China sent 24,226 students to Russian universities, becoming the largest source of international students outside the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and accounting for 8 percent of the foreign students in Russia. For comparison, 20 percent of students were from Kazakhstan and 16 percent were from Uzbekistan. About three-quarters of Chinese students major in humanities and the social sciences (especially languages), with the proportion of science and engineering students being significantly lower. Charts 1 and 2 show the rapid growth in the number of Chinese and Russian students studying in the other country.

In 2020, about 300 inter-school cooperation agreements were signed between Chinese and Russian universities, covering, among other things, educational projects, language teaching, and scientific research. By 2019, China established 19 Confucius Institutes in Russia, and 35 Russian Cultural Centers were founded in Chinese cities. Endorsed by President Xi and President Putin, the Shenzhen municipal government, Beijing Institute of Technology, and Lomonosov Moscow State University jointly established the Shenzhen MSU-BIT University (SMBU) in Shenzhen in 2016. The university began to accept undergraduate and graduate students in master’s programs in 2017 and doctoral students in 2018. Former Shenzhen Mayor and now Heilongjiang Party Secretary Xu Qin (1961), a political rising star in the Xi era, was instrumental in the establishment of this joint university.

It remains to be seen whether China’s growing educational exchanges with Russia will lead to more Russian-educated elites in the political leadership in the future. As for now and the near future, Western-or-U.S. trained returnees have been disproportionately well represented in the Party leadership, as shown in the previous article. Among the contenders for membership in the next Politburo, only one leader, Fujian Party Secretary Yin Li (1962), is a Russian-educated returnee. Yin received a doctoral degree in public health from the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences (1988-1993). Yin was also a visiting scholar at the Harvard School of Public Health from 2002-2003.

Also noticeably, some of the influential conservative opinion leaders in present-day China have lengthy experience in Russia. The internationally famous social media guru Hu Xijin (1960), the editor-in-chief of the Chinese government-sponsored Global Times from 2005 to 2021, is a good example. Hu attended the Institute of International Relations in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) from 1978-1982. Over the following four years, he served as an instructor in the 87153 Unit of the PLA. In 1989, he obtained a master’s degree in Russian literature from Beijing Foreign Studies University and began to work at People’s Daily, the propaganda organ of the Chinese Communist Party. He was soon dispatched to Moscow and witnessed the historic moment of the disintegration of the Soviet Union. From 1993 to 1996, Hu served as a reporter in Yugoslavia, covering the Bosnian War. Hu also later spent much time in the Persian Gulf, covering the Iraq war.

Although from time to time, Hu challenged or offended people across the political spectrum, including the Party establishment, he has been seen as the country’s leading “wolf warrior” targeting the United States. Most recently, he even shared a widely circulated Twitter post that asserted that “If a U.S. fighter jet escorts Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, it is an aggression. The PLA has the right to forcibly drive away Pelosi’s plane and the U.S. fighter jet. …If the drive is ineffective, they can be shot down.”

While one may not take Hu’s characteristic sensationalism seriously, some other figures in the mainstream official media outlets are arguably even more impactful. Lü Yansong (1967), who spent many years in Russia as a People’s Daily correspondent (1991-1993) and chief correspondent (2001-2005), was recently appointed to be editor-in-chief of Xinhua News Agency.

During the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, Lü Yansong and his wife were stationed in the Chinese embassy in Yugoslavia. Three other Chinese reporters were killed by the bomb that hit the Chinese embassy, and Lü Yansong and his wife survived from the disaster. Lü was deputy director of the Central Publicity Department of the CCP before his current position, and he is a delegate for the 20th Party Congress. He may be able to obtain alternate membership on the new Central Committee this October.

It is unclear whether China’s officials with substantial experience in Russia, represent a trend or just individuals’ cases. But the growing number of Chinese military officers trained in Russia is a far more important phenomenon that deserves attention from China watchers. This will be the focus of the next article.