Numerous Pekingologists –– scholars of Chinese elite politics –– have emphasized it before, and they will emphasize it again: the key to understanding the formation and orientation of the national leadership in present-day China is to pay greater attention to the dynamic developments in the provinces. This is not necessarily related to the sheer size and population of the country or the old Chinese saying “Mountains are high and the emperor is far away.” Rather, this assessment largely reflects the growing importance of central-provincial relations and the trend to recruit Party elites from province-level leadership during the reform era.

China has 31 province-level administrations, including 22 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, and 4 municipalities directly under the central government. They are all enormous socioeconomic entities. Provincial chiefs (Party secretaries, governors or mayors) are often leading candidates for powerful offices in Beijing, affirming the trend of recent decades that provincial official posts are key stepping stones to national leadership positions. The geographic distribution or regional representation in the Central Committee (CC), Politburo, and Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) is often a revealing indicator of the political landscape and policy trajectory of the Party leadership.

China’s provincial leadership arena is, therefore, both a training ground for national leadership positions and a competitive terrain that political elites must traverse. Given that their responsibility to govern has coincided with an increasingly challenging socioeconomic environment, both at home and abroad, provincial chiefs now carry much more weight than ever seen before in the history of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Understanding these factors is essential for analyzing and forecasting the leadership lineup at the upcoming 20th Party Congress.

Growing prominence of provinces

It is often said that a province is to China what a country is to Europe. In fact, Chinese provinces have much larger populations than most countries in the European Union (EU). According to population data released by the National Bureau of Statistics of China in 2020, China’s five largest provinces –– Guangdong (126 million), Shandong (102m), Henan (99m), Jiangsu (85m), and Sichuan (84m) –– are all, respectively, more populous than Germany (83m), the largest nation in the EU. Moreover, Guangdong’s population is the same as Japan’s (126m), which is currently ranked eleventh in the world for population size.

The economic outputs of these Chinese provinces are more than substantial. At the beginning of 2022, the total GDP of Guangdong Province (US$1.93 trillion) surpassed that of South Korea ($1.91 trillion), the country with the tenth largest GDP in the world. One Chinese official source even highlighted that, in terms of economic prominence, Guangdong Province is not far behind Italy ($2.3 trillion) and Canada ($2.2 trillion), countries with the eighth and ninth largest GDPs. Additionally, if included in the ranking of GDPs by country, nine Chinese provinces (Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong, Zhejiang, Henan, Sichuan, Hubei, Fujian, and Hunan) would fall in the same range as the top 20 economies in the world. Lastly, according to data from the World Bank in 2020, Hunan Province’s GDP ($0.71 trillion) surpassed Saudi Arabia’s ($0.70 trillion), a country ranked 20th in the world.

China’s provincial chiefs, like top leaders in European nations and East Asian neighboring countries, are constantly concerned about economic development. They have often coped with myriad challenges, such as unemployment, inflation, distributive justice, social stability, technological competition, environmental protection, food safety, and public health, as well as the welfare of those residing in their jurisdictions. China’s integration into the global economy over the past several decades means that its provincial chiefs must also be fervently engaged in international trade and investment, even though they do not directly play a role in foreign policy.

Understandably, the expectations of provincial chiefs – both administratively and politically – are now far higher than ever before. The occupational backgrounds and career experiences of provincial chiefs have also correspondingly undergone profound changes. The longstanding norm of advancing careers step-by-step from county to prefecture to municipality to province is no longer a dominant pattern. Instead, a significant number of provincial chiefs today have primarily advanced their careers as CEOs or senior executives of major state-owned-enterprises, most notably Xinjiang Party Secretary Ma Xingrui (1959), Zhejiang Party Secretary Yuan Jiajun (1962), Hunan Party Secretary Zhang Qingwei (1961), Liaoning Party Secretary Zhang Guoqing (1964), and Shandong Governor Zhou Naixiang (1961). The first three individuals have substantial leadership experience in China’s aerospace industry.

Also, Shandong Party Secretary Li Ganjie (1964) and Beijing Mayor Chen Jining (1964) are China’s leading experts on environment protection as well as proponents of alternative energy. Fujian Party Secretary Yin Li (1962) and Hainan Party Secretary Shen Xiaoming (1963) are medical doctors by training and have also worked in the field of public health for many years. The promotion of these top provincial leaders with distinct professional expertise in present-day China deserves greater attention. Most of these provincial chiefs are widely seen as rising stars with great potential for further advancement in Xi Jinping’s third term. The fact that these well-accomplished individuals are now serving in province-level leadership positions bolsters the integral role that provinces play in Chinese politics.

Stepping stones to the national leadership

The fact that province-level leadership experience often serves as a stepping stone to holding top national posts is, of course, not new. Deng Xiaoping’s economic reform strengthened regional autonomy and placed more emphasis on the provincial administrative experience of Party officials. Counting the positions of deputy Party secretary, vice governor (or vice mayor) as well as including provincial Party standing committee members, the percentage of Politburo members with provincial leadership experience rose sharply during the reform era: from 55 percent of members in 1992 to 68 percent in 1997 to 83 percent in 2002. Of the three Politburos in the successive two decades, 76 to 80 percent of members had provincial leadership experience.

More significantly, top leaders usually worked as provincial Party secretaries before moving to Beijing to serve on the national decision-making bodies in Zhongnanhai and before being anointed “heir apparent.” For example, Jiang Zemin was promoted to general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1989 from Shanghai Party secretary; Hu Jintao served as Party secretary in both Guizhou and Tibet before being promoted to the PSC in 1992. Like Hu, Xi Jinping moved to Beijing to become “heir apparent” in 2007 after serving as Party secretary first in Zhejiang and then in Shanghai.

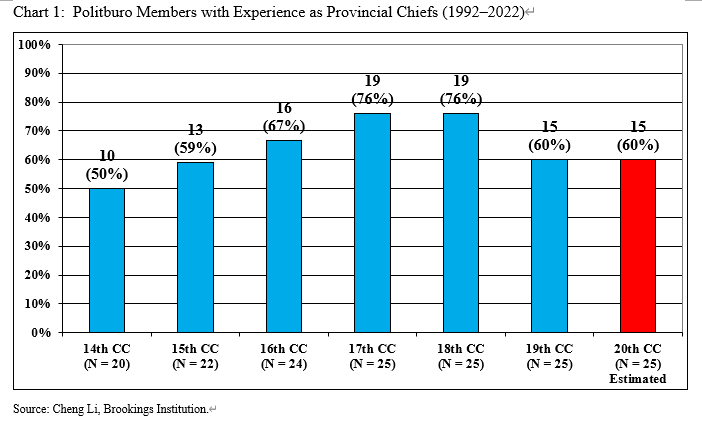

In the current Politburo, 15 out of 25 members (60 percent) have experience as provincial chiefs. In fact, this percentage is lower than those of the three previous Politburos (see Chart 1), largely because leaders with careers in government think tanks, Party functional departments, foreign affairs, and financial affairs have also obtained Politburo seats (these recruitment channels for the national leadership will be discussed later in the series). Nevertheless, the trend of having a majority of top CCP leaders with provincial chief experience will likely continue for the foreseeable future. Based on my assessment of the prospective candidates for the next Politburo, I forecast that the 20th Politburo will likely maintain the same percentage of members with provincial chief experience.

On the three most recent PSCs, only one member on each PSC had not served as a provincial chief (Wen Jiabao on the 17th PSC, Liu Yunshan on the 18th PSC, and Wang Huning on the 19th PSC). It has also become a norm that six Party secretaries from province-level administrations (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, Guangdong, and Xinjiang) concurrently serve on the newly formed Politburo, as was the case for both the 18th and 19th Party Congresses. Some of them have advanced to become members of the PSC after serving in the most pivotal province-level entities. The recurring trend for China’s top leaders to have robust province-level leadership experience illustrates the importance of this trajectory to the pinnacle of power.

Regional representation

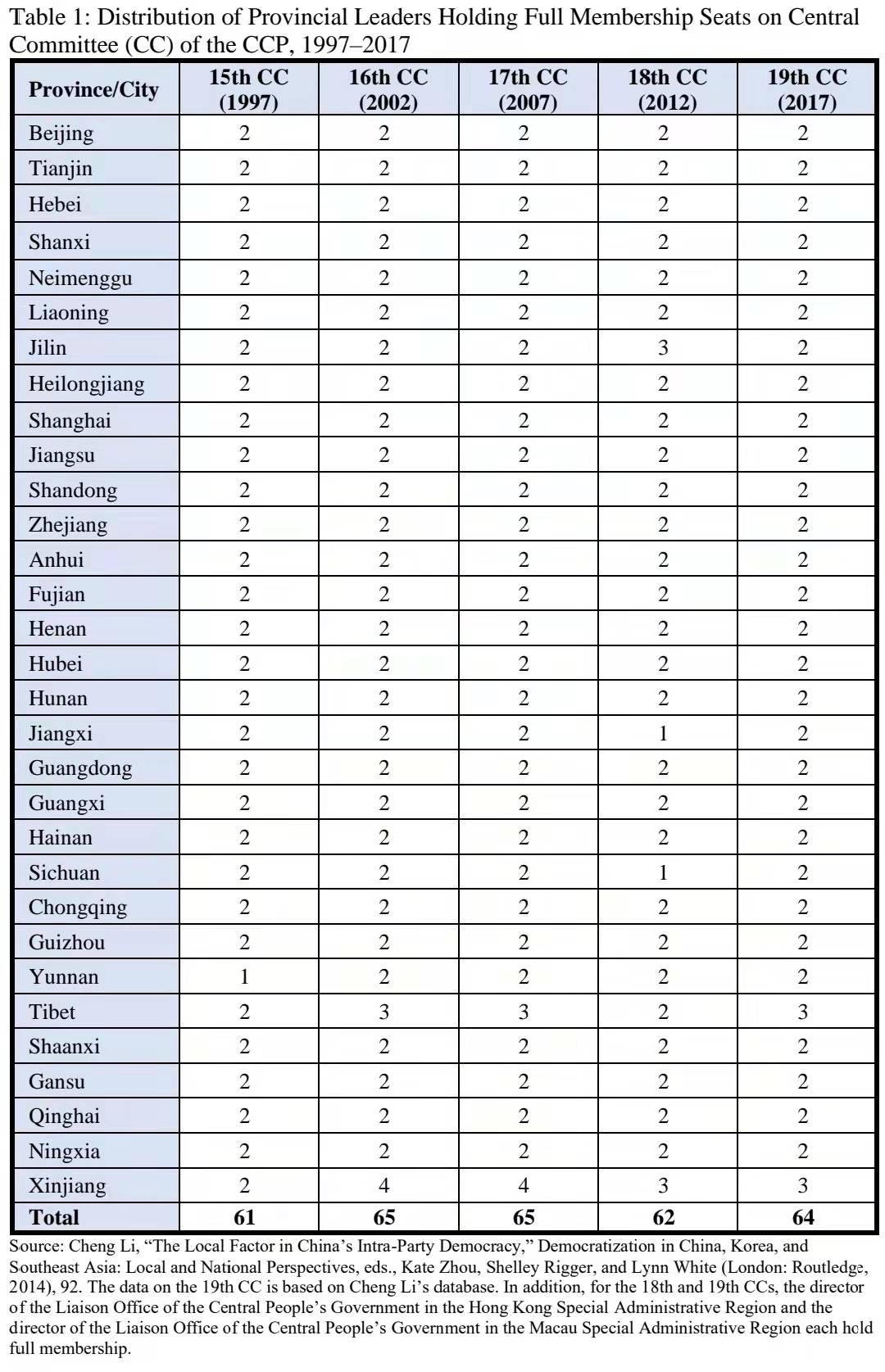

Like many other countries, regional representation on national leadership bodies is just as important of an issue for Chinese domestic politics. Since the 15th Central Committee in 1997, each province-level administration has held two full membership seats (usually occupied by the provincial Party secretary and the governor or mayor) on the CC. Provincial chiefs may later be promoted to the central government or transferred to other provinces or cities. But when CC members are initially selected, seats are allocated according to this norm.

Table 1 shows that, with very few exceptions, regional representation has been continually stable for the past five CCs between 1997 to 2017. Regions with a high ethnic minority population like Tibet and Xinjiang are not constrained by these norms. They can have more than two seats. This norm was observed for the 19th CC, with each province-level entity attaining two full membership seats, while Tibet and Xinjiang each had three.

The reason that only one full member position was allocated to Yunnan in 1997 as well as Jiangxi and Sichuan in 2012 is that multicandidate elections were instituted for the Central Committee. For example, the governors of Sichuan and Jiangxi failed to attain full membership on the 18th CC, leaving these two provinces with only one representative each. It is also interesting to note that the Politburos elected in both 2012 and 2017 each had at least one member who had worked extensively in one of China’s major geographic regions: the northeast, north, northwest, east, south central, south, and southwest.

The equal regional distribution of full membership seats on the CC profoundly affects the relationship between the central party-state and local authorities. Top national leaders have a vital interest in seeing their protégés attain provincial leadership, especially in the major cities and provinces. Subnational leaders in areas that have benefited from market reforms want to maintain the policy orientation that best favors their interests, while those in disadvantaged regions favor members of the central leadership who emphasize common prosperity and value a more balanced geographical distribution.

Not surprisingly, a recent report published by scholars at Tsinghua University characterizes members of the province-level Party Standing Committees as the key “reserve” of Chinese state leaders. Furthermore, most of the current 62 provincial chiefs were appointed to their posts in the past couple of years, and many of them will be first timers on the 20th CC. The next article in this series will analyze the ongoing reshuffling of the provincial Party standing committees. This analysis can help unveil the leadership composition, characteristics, and trends expected at the upcoming 20th Party Congress.